|

| Rollei 16 |

Franke & Heidecke, best known for the medium format Rolleiflex and Rolleicord cameras,

before producing their first 35mm camera, brought out the

Rollei 16, a subminiature camera using single perforated 16mm film. The Rollei 16 was made between 1963-1967 and was followed by the Rollei 16S, essentially the same camera with minor changes, made until 1972 - the year that Kodak introduced the 110 cartridge format. Three years after the Rollei 16, the

Rollei 35 appeared, an extremely compact full-frame 35mm camera. The popularity of high-specification 16mm subminiature cameras no doubt suffered from the emergence of compact 35mm cameras, while, in general terms, the cheaper type of 16mm cameras were supplanted by the 110 format.

Beautifully designed, constructed, and finished, the Rollei 16 has two major drawbacks for continued, contemporary use, designed into the camera. The first of these, common to subminiature cameras before the 110 format cartridge, is that the Rollei 16 uses a

particular type of cassette, sometimes called the Rada 16 (the format itself appear to have been referred to as Super 16), which, unusually, included the facility to rewind the film. Negative size is 12x17mm; the camera takes 18 exposures on a roll (the cassette takes about 50cm of 16mm film). The same cassette was also used for Wirgin's subminiature camera, the

Edixa 16 and its Franka and Alca named variants. This cassette is now rare: the last online auction I followed topped out at €25 for just one cassette. Secondly, the film advance requires perforations to advance the film. Restricting the Rollei 16 to perforated 16mm film ensures that cut down or unperforated film can't be used, unlike almost every other 16mm subminiature camera that I am aware of (the design of the Kodak 110 cartridge being a separate case). The Edixa 16, which shared the same cassette design as the Rollei 16 (but which can take unperforated film), came to market a year earlier than the Rollei 16; perhaps Franke & Heidecke took the decision to design their subminiature camera to fit this existing camera. Intriguingly, the Edixa 16 was designed for Wirgin by

Heinz Waaske, who later joined Franke & Heidecke; Waaske was the designer behind the Rollei 35, and the Rollei 110 and 126 format cameras.

|

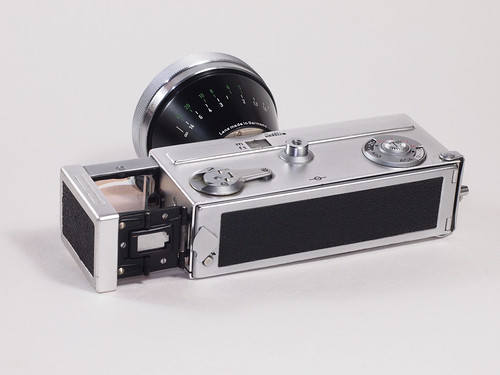

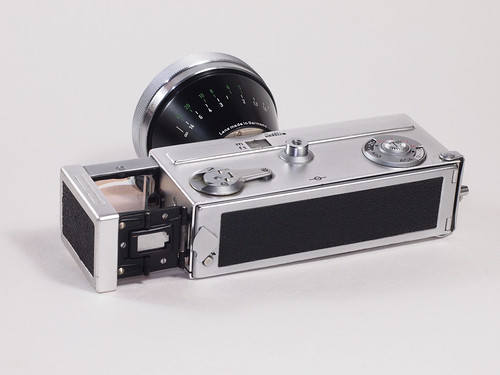

| Rollei 16 closed |

The Rollei 16 is relatively large for a subminiature camera - 110mm wide when in the closed position, by 43mm deep at its bayonet mount, and 35mm high at its shutter release (when open the camera is 135mm wide). The camera boasts a focussing f2.8 25mm Tessar, reputedly one of the very best lenses for subminiature photography (according to

Cameraquest). Part of the camera's length is taken up by the built-in Gossen-branded selenium light meter, this provides the Rollei 16 with automatic exposure, still a fairly advanced feature for 1963. The light meter has a range from 12 to 200 ASA; the dial is also marked with DIN, unsurprisingly for a 1960s German-made camera. The dial includes an adjustment wheel inside this with minus adjustments for filters (or for backlit exposures - there are no corresponding 'plus' adjustments, although this can be done with changing the film speed setting where possible within the existing range). The adjustments are marked -1 -2 -3. The programmed exposure works at a range from 1/30th at f2.8 to 1/500th at f22 (exposure values 8-18). The manual has a diagram showing the exposure values divided into half steps, and the automatic exposure is designed to achieve faster shutter speeds with increasing brightness before then reducing the aperture. Next to the lens is a small 'signal window' - which appears to be a tiny, second selenium meter that powers a green LED to indicate exposure which shows in a small prism in the viewfinder.

The light meter still works well enough after more than fifty years; using black and white film, there's enough tolerance in the film to ensure well-exposed negatives. 200 ISO as maximum film speed does seem a little slow for the time of production, although, due to only using perforated 16mm, the fastest film I've used with the Rollei 16 is Eastman Double-X. By contrast, the

Mamiya-16 Automatic from 1959 has a meter with a highest film speed setting of 1600 (at a time when I believe that the fastest film available would have been the 800-speed Ilford HPS); perhaps the Rollei 16's top film speed reflects that the small size of the negative dissuades one from using too fast a film.

|

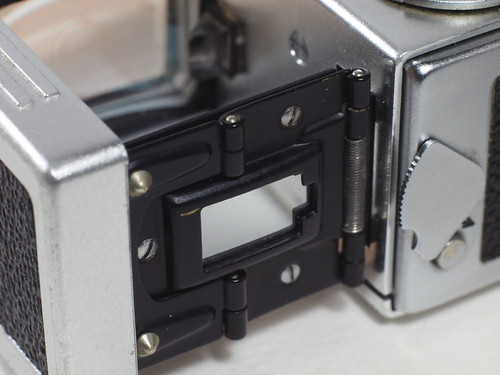

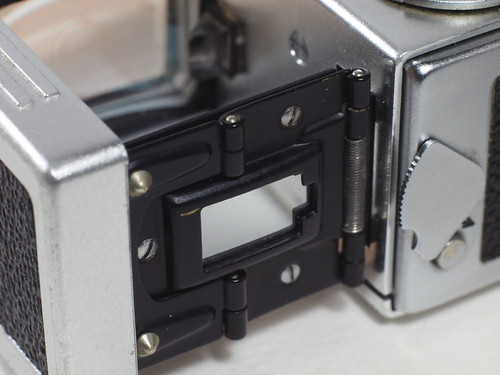

| Rollei 16 opened for loading |

The back of the camera has a small pivoting lock; opening this shows a long pressure plate inside the camera back. The camera does not have a take-up spool of any kind: the film simply coils upon itself into the chamber on the right hand side, guided by two curved pieces of plastic. The push-pull film advance works by a sliding claw engaging with the perforations: when loading, the film is placed under two small round 'buttons' and the camera back then closed.

Excluding 110 cartridge cameras, the Rollei 16 is the only subminiature camera I am aware of that needs perforations to advance film. This means that it

could be used without a cartridge: a length of 16mm could be loaded into the camera's supply-side chamber in the dark. However, I used

cut-down supply-side Kiev cassettes. These fit inside the Rollei 16, but cannot be rewound, meaning that I had to remove the film from the camera in the dark and then manually wind the film back into the cassette. Without the right cassettes, this limits using the Rollei 16 to a single roll of film at a time, unless one carries a changing bag around for the purposes of reloading the camera.

|

| Rollei 16 loaded with cut-down Kiev subminiature cartridge |

The push-pull action only advances the film after an exposure has been made. The viewfinder is released with a small lock on its underneath. The rear portion of the viewfinder has an ingenious folding design for closing it against the camera body; the front section pushes in to create a cover for the lens (and, it appears, the signal window too). The shutter release button is the same size as that for a much larger camera, centrally located on the camera body and threaded for a cable release. Focus is by estimation in metres and feet, with a small geared wheel above the lens for setting focus: according to the manual, the range of values which appear in the window indicates

minimum depth of field, which logically must be for the maximum aperture of f2.8. The setting 4m/14ft is picked out in red as a hyperfocal distance for snapshots. The Rollei 16's parallax correction, rather than simply providing additional frame lines, actually tilts the front part of the viewfinder to change the position of the reflected frame lines in accordance with the subject distance.

|

| Rollei 16 viewfinder detail |

As well as a parallax-corrected viewfinder, the Rollei 16

also has what amounts to an exposure lock, achieved by partly depressing the shutter button - the manual states: "Do not touch the button too soon. The slightest pressure on the button selects the measured exposure value." This suggests a 'trap-needle' construction to the camera's automatic exposure.

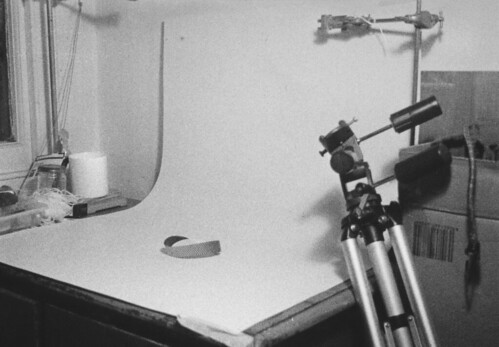

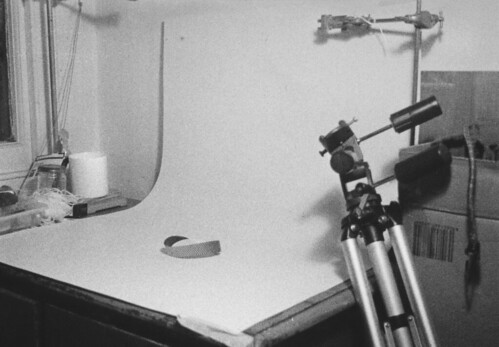

For this post, the photographs illustrating it are all scanned from prints made in darkroom: given the assertion that the Rollei 16's Tessar is one of the best lenses on a subminiature camera, rather than use a flat bed scanner on the negatives, I wanted to see how good the results might be. Given the small size of the negatives, grain is of course pronounced, however, and the slowest film that I shot with the Rollei 16 was

Plus-X. The prints were made around 5x7 inches, big enough for the negative size. The two examples below were chosen to make a fairly obvious comparison: the

Double-X film is by no means inherently fine-grained, but the Eastman 4-X film, originally 500 ASA, must be around thirty years old, if not older, and this shows.

|

| Eastman Double-X at EI 125 developed in Ilfotec LC29 |

|

| Eastman 4-X at EI 20 developed in R09 One Shot |

The 25mm Tessar lens has a close focus of 0.4m or 1.3 ft - not quite as close as the Mamiya-16 Automatic's 1 foot distance, but excellent nonetheless. One of the accessories for the Rollei 16 was a measuring chain, useful for calculating near focus. The viewfinder's parallax correction is a genuine help here too, far better than a typical set of extra lines in the viewfinder to indicate the framing of a close subject. In the second of the two images below, the focus was set to 0.4m and the central framing was almost perfectly represented in the viewfinder.

|

| Rollei 16 with Eastman Double-X film |

|

| Rollei 16 with Kodak Plus-X |

The Rollei 16 has two sets of viewfinder lines: a solid outline; inside this outline are four corner marks indicating a smaller, central frame. This central frame is used with one of the accessories made for the Rollei 16, the

Tele-Mutar supplementary lens; the wide-angle Mutar utilises the entire viewfinder frame, i.e. that outside the solid frame lines for the 25mm lens. Like the Rollei 16's lens, these accessory lenses were also made by Zeiss. The Mutars fix to the bayonet fitting around the lens (also used for a number of filters), with a black dot to indicate the correct position to attach these. The Mutars also have cut-out indents so as not to block the signal window. Shortly after acquiring my Rollei 16, I found both Mutars on a well-known auction site, but lost out on the wide-angle version. Attaching the Mutar lenses significantly increases the weight and bulk of the Rollei 16, making the camera very front heavy.

|

| Rollei 16 with 1.7x Mutar |

The Mutars can be attached to the bayonet fitting in two orientations: one way up, the Mutar's focus scale is in meters (in red), read from the top of the camera; attached the other way, the scale in feet (in green, seen below) is on top. The scale is used to convert focus distances: the coloured numbers indicate the focus setting with the Mutar lens which is then translated to the white number to be set on the camera; the depth of field is indicated between three white lines, or more accurately, between the two white lines either side of the line that the focus is set to. Close focus with the 1.7x Mutar is limited to 1 meter or 3.5 feet. The 1.7x Mutar makes an equivalent focal length of 42mm, an angle of view of 27º (by comparison, the 0.6x Mutar has an equivalent focal length of 16mm and an angle of view of 65º - the 25mm Tessar on its own has a 45º angle of view). The manual also instructs the user to reduce the film speed setting by 'one step' or 1 DIN value, something that I didn't adhere to when using the Mutar for the photographs on this post.

|

| Rollei 16 with 1.7x Mutar |

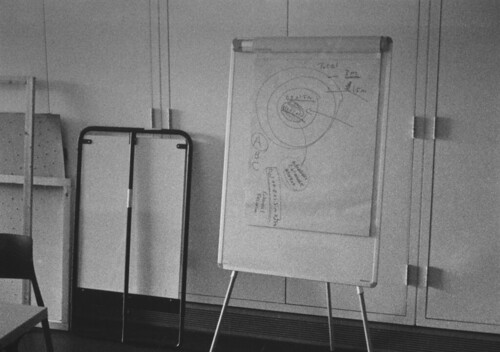

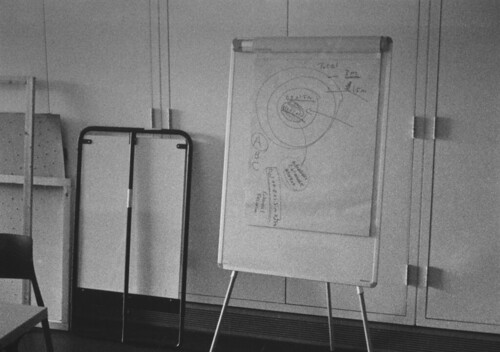

The two pairs of images below give some indication of the changing angle of view, first with and then without the Tele-Mutar lens. It's possibly just discernible in the prints that the supplementary lens reduces the effective aperture by a small amount, something not entirely compensated for in the printing of the negatives, but this wasn't something I especially noticed; no doubt the film's latitude compensated for this.

|

| Rollei 16 with Eastman Double-X film at EI 125 |

|

| Rollei 16 with Tele-Mutar and Eastman Double-X film at EI 125 |

The second pair of images below appear to show some flare in both shots, with and without the Mutar; this might be exaggerated thanks to the subject, with a dark foreground, with the shade giving way to bright reflected light behind. Being heavy and awkward, and needing to convert focus distances when using the Mutars, does take away some of the benefits of using a subminiature camera in the first place (carrying

both around in their cases with the camera itself starts to make the Rollei 16 less than pocketable - and one can add the tripod and flash adaptors too, as well as a range of filters), yet these can be a useful addition to the Rollei 16, designed as it was to be a subminiature

system as a whole.

|

| Rollei 16 with Kodak Photo Instrumentation film |

|

| Rollei 16 with Tele-Mutar lens and Kodak Photo Instrumentation film |

Although the Rollei 16 has does have fully automatic exposure, controlled by its light meter, what is also not often mentioned about the camera is that it is possible to use the flash settings for manual exposure, albeit at a single shutter speed, 1/30th.

|

| Rollei 16 bottom plate with flash/B aperture selection and frame counter |

The dial on the camera's bottom plate rotates through 360º (it has a small lock switch), with two 'A' (for automatic) positions; with aperture settings on each side of the dial, one set of apertures is for use with flash, the other set is marked 'B' for bulb setting. Therefore, it is possible to have some form of override, by using the flash setting for shutter speed and then selecting the appropriate aperture. The image below was shot using the flash setting (without a flash) at the maximum aperture of f2.8. On the A setting, if the green LED

does not appear, the shutter will still fire (there's no red flag as with the

Olympus Pen); I assume that the shutter and aperture will be set to provide maximum exposure possible, 1/30th at f2.8.

|

| Rollei 16 with Eastman Double-X film at EI 125 |

I also shot the camera in 'B' mode for long exposures. The Rollei 16 doesn't have a tripod socket (a separate tripod adaptor was available); with the flash/B setting wheel and the frame number window both protruding from the bottom of the camera, without a flat base, it's harder to balance the camera on a flat surface for long exposures (it might be easier in portrait orientation, with the viewfinder end of the camera being quite flat, but then the pressure on the shutter button relative to how the camera is rested might still move the camera anyway). For the photograph below, I balanced the camera for a few seconds on the rounded top of a bollard while the shutter release was depressed.

|

| Rollei 16 with Eastman Double-X film at EI 125 |

The film advance stops when the frame counter reaches 18, which means that it isn't possible to load a longer length of film into the camera (the frame counter resets on opening the back of the camera; by contrast, the

Mamiya-16 Automatic's frame counter simply rotates around again after 18 shots and I've often got frames of mid- to high twenties while the

Kiev-30M's frame counter stops at 25 but the film can be advanced further). It's just possible to get more than 18 shots on a roll however, squeezing in one, two or even three shots

before the frame counter reads 1, but there's always a risk that these shots may be partly or wholly obscured.

Ideally, for a subminiature camera, to best show off what's possible with the Rollei 16, I would have liked to have shot a slow, fine grain film, but for this post, limited to perforated 16mm film (and having an innate preference for black and white over colour) I shot four different film stocks: Eastman Kodak currently produces just one black and white film stock,

Double-X, in 16mm, while of the three other Eastman Kodak stocks, two are discontinued, and the third is a 'special order' stock. This, as much as the proprietary cassette, severely limits using the Rollei 16 today (it might be possible to reverse engineer a rewinding cassette for the camera, with some ingenuity but accurately perforating 16mm film is a problem with a different order of magnitude). Cassette and perforation issues notwithstanding, using the Rollei 16 itself - and being able to compare the experience with that of other subminiature cameras - makes one appreciate its conception, the quality of its design and construction, its easy to use controls, the automatic exposure, push-pull film advance, and the large, clear viewfinder with its parallax correction.

|

| Rollei 16 with Eastman 4-X |

|

| Rollei 16 with Kodak Plus-X |

|

| Rollei 16 with Eastman Double-X at EI 125 |

|

| Rollei 16 with Eastman Double-X at EI 200 |

Edit 18/4/19: See also Rollei 16 Cassettes

Sources/further reading

Rollei 16 on Submin.com

Rollei 16 Manual

Kameramuseum's page on the Rollei 16 (German)

Cameraquest's review of the Rollei 16S

Rollei 16 on Camera-Wiki