Paper Cinema; silver gelatin prints, 9.5x12 inches each

Paper Cinema; silver gelatin prints, 9.5x12 inches each

The text in the two photographs reads:

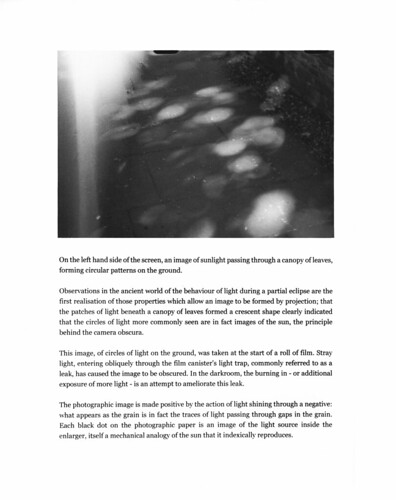

On the left hand side of the screen, an image of sunlight passing through a canopy of leaves, forming circular patterns on the ground.

Observations in the ancient world of the behaviour of light during a partial eclipse are the first realisation of those properties which allow an image to be formed by projection; that the patches of light beneath a canopy of leaves formed a crescent shape clearly indicated that the circles of light more commonly seen are in fact images of the sun, the principle behind the camera obscura.

This image, of circles of light on the ground, was taken at the start of a roll of film. Stray light, entering obliquely through the film canister's light trap, commonly referred to as a leak, has caused the image to be obscured. In the darkroom, the burning in - or additional exposure of more light - is an attempt to ameliorate this leak.

The photographic image is made positive by the action of light shining through a negative: what appears as the grain is in fact the traces of light passing through gaps in the grain. Each black dot on the photographic paper is an image of the light source inside the enlarger, itself a mechanical analogy of the sun that it indexically reproduces.

***

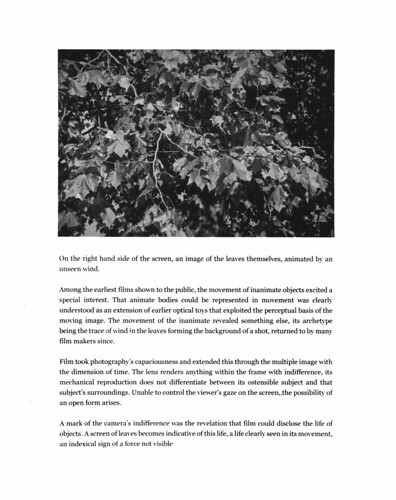

On the right hand side of the screen, an image of the leaves themselves, animated by an unseen wind.

Among the earliest films shown to the public, the movement of inanimate objects excited a special interest. That animate bodies could be represented in movement was clearly understood as an extension of earlier optical toys that exploited the perceptual basis of the moving image. The movement of the inanimate revealed something else, its archetype being the trace of wind in the leaves forming the background of a shot, returned to by many film makers since.

Film took photography’s capaciousness and extended this through the multiple image with the dimension of time. The lens renders anything within the frame with indifference, its mechanical reproduction does not differentiate between its ostensible subject and that subject's surroundings. Unable to control the viewer's gaze on the screen, the possibility of an open form arises.

A mark of the camera’s indifference was the revelation that film could disclose the life of objects. A screen of leaves becomes indicative of this life, a life clearly seen in its movement, an indexical sign of a force not visible.

***

Notes

One

On the left hand side of the screen: In the photographic print itself, the screen referred to is not explicit in the image: the reader of these two photographs is being asked to imagine a screen, the description that follows makes it clear that the image on the print above the text is that to which the text refers. The left and right descriptions are orientations understandable in relation to one each other in the exhibition display.

an image of sunlight passing through a canopy of leaves, forming circular patterns on the ground: In the Northern Hemisphere this effect is most notable during the summer months; the sun needs to be sufficiently high in the sky to project circles of light on the ground, at lower elevations, these circles become oblique. The distance between the canopy and the ground also affect the appearance of the circular patterns: as with a pinhole, there is an optimum focal length for the formation of an image.

Observations in the ancient world of the behaviour of light during a partial eclipse: In the fourth century BCE, Aristotle observed this behaviour:

"The image of the sun at the time of the eclipse, unless it is total, demonstrates that when its light passes through a narrow, round hole and is cast on a plane opposite to the hole it takes on the form of a moon-sickle. The image of the sun shows this peculiarity only when the hole is very small. When the hole is enlarged, the picture changes..."

Aristotle, 'On The Form Of The Eclipse'

are the first realisation of those properties which allow an image to be formed by projection: At its simplest, this is the property that light waves travel in a straight line. If rays of light are permitted to project onto a surface through a sufficiently small aperture, an inverted image is drawn on that surface.

that the patches of light beneath a canopy of leaves formed a crescent shape clearly indicated that the circles of light more commonly seen are in fact images of the sun: During the total eclipse of 2017, visible across North America on Monday 21st August (a week and a day after the photograph of the patches of light was shot), images of the crescent shape of projected light through the leaves of trees either side of totality was seen across social media with a sense of astonishment remarkable for such a natural phenomenon, particularly in the context of a total solar eclipse itself.

the principle behind the camera obscura: The application of the Latin word

camera in English - and many other languages - to describe a device which takes photographs retains this link to the dark or

obscured room or

chamber. Many cameras obscura utilise a lens to form a sharper, brighter image, but the principle remains the same.

This image, of circles of light on the ground, was taken at the start of a roll of film: The partial visibility of perforations at the top of this image are evidence of its physical substrate. The flexible roll film was designed for the ease of shooting a succession of still images without the need to reload a camera; after early experiments with both paper and glass cylinders, flexible celluloid film was adapted for the first moving image cameras, and perforations were introduced for the intermittent motion required to reproduce a succession of correctly registered still images that could then recreate motion when played back. Perforated 35mm motion picture film stock was reused for still photography, popularised by small format cameras. Less common, other still cameras used other perforated motion picture film stocks.

Stray light, entering obliquely through the film canister's light trap, commonly referred to as a leak: Light is seen as pernicious, wanting to gain ingress, yet it is a substance that can be trapped. In photography, analogies between light and water abound: a light

source itself; light 'pours in' through leaks; understanding the relationship between aperture and shutters speed in exposure is likened to turning on a tap, or water passing through a sieve; liquid photographic emulsion is also known as liquid light. There are others.

has caused the image to be obscured: Obscured here in the sense of obliterating the detail in the image, the additional exposure of unwanted light from a source other than the lens, passing over the surface of the film, reduces the detail of the image forming on the surface itself.

In the darkroom: In a mirroring of the process of image formation inside the dark chamber of the camera, after development of the exposed film into a negative, returning to another dark chamber is required to create the final, positive image.

the burning in - or additional exposure of more light - is an attempt to ameliorate this leak: 'Burning in' is another analogy or metaphor; light here, part of the spectrum of electromagnetic radiation, is connected to heat, and this metaphorical heat in connected to the darkness of the image. The darkroom techniques of

dodging and

burning remain familiar through their emulation as digital tools in image-manipulation software.

The photographic image is made positive by the action of light shining through a negative: As silver halide salts darken with exposure to light, an image formed is inverted in its tonal range. Inverting this a second time provides the required positive image. Demonstrating linguistic logic, here two negatives do make a positive. All photographic processes which produce an image rely on this phenomenon. Although the Daguerreotype is sometimes described as a positive process, the images are not strictly positive, rather the angle of reflection from the polished silvered surface determines whether the image appears positive or negative.

what appears as the grain is in fact the traces of light passing through gaps in the grain: Grain is another metaphor; photographic grains are clumps of silver halide crystals reduced to metallic silver by the process of development. The quality of grain only became prominent when negatives began to be printed by enlargement, dependent on many factors, but chiefly the enlargement ratio and the film's sensitivity to light; the word printing itself is suggestive of the direct contact between the negative and positive surfaces: with enlargement, the photographic print really becomes something else. In the photographic print itself, the grain of the light sensitive paper remains below the threshold of perception as it is not enlarged.

Each black dot on the photographic paper is an image of the light source inside the enlarger: In the 19th century, most photographs made using the negative-positive process were contact printed by daylight; with larger negatives, prints by contact persisted well into the 20th century. Although enlargers did exist, exposure times with the low sensitivity emulsions then available would result in prohibitively long exposure times. Printing by enlargement needed faster emulsions, faster emulsions made the possibility of smaller format cameras viable; early roll-film formats provided relatively large negatives for contact printing. The use of 35mm motion picture film for still images broke this link, making enlargement of the negatives necessary.

a mechanical analogy of the sun: In 1826, Nicéphore Niépce devised the term

héliographie - sun-drawing - to describe his experiments with creating images using light-sensitive materials, making explicit photography’s relationship to the sun. Eadweard Muybridge used the name 'Helios' when he began his career as a photographer, and called his business, 'Helios Flying Studio'.

that it indexically reproduces: In the semiotic system of Charles Pierce, signs can be categorised in three different ways according to their relationship to the sign's

referent - the reality to which the sign points. The photograph is an

index in having a direct relationship to the optical phenomenon it reproduces: light, reflecting from the subject, strikes the photographic emulsion, and causes an image to be formed. In Peirce's terms, photography also fulfils the condition of the

icon: the icon is a sign which resembles its referent: photographs tend to resemble their referent in visual terms due to their indexical construction.

***

Two

On the right hand side of the screen, an image of the leaves themselves, animated by an unseen wind: The first image, of circular patterns of light caused by the sun penetrating a canopy of leaves, is joined by a second image, reading from left to right, a spatial juxtaposition in an analogy of the principle of cinematic montage. The wind which animates the leaves - this animation merely inferred by the still image - in unseen in the sense that the actual movement of air is not visible, but its indexical effects on the leaves can been seen.

Among the earliest films shown to the public: Films had been exhibited by projection by the Lathams' Lambda company in New York in May 1895; by the Skladanowsky brothers in Berlin in November; and by the Lumière Brothers in Paris in December (all had previous private or press showings earlier that year). Photographic moving images had previously been shown in Thomas Edison's

kinetoscope, the peep-show box seen by a single viewer at at time; cinema as a collective experience - as the institution that it would become - required projection, to which Edison was initially resistant. The collective experience would prove to be transformative.

The Lumières' first public programme exhibited ten films, all 'actualités'. The Lumières'

cinématographe, camera, printer, and projector in one, was small, portable, and hand-cranked, thus able to go anywhere, out into the world - and able to encounter the movement of inanimate objects. Such effects were not available to Edison: unsurprisingly, his camera was powered by electricity, and therefore not portable in practical terms at the time. Instead, Edison built the Black Maria, the first film studio, which dictated the content of his kinetoscope reels; other early film-makers conceived of film's possibilities in similar terms to Edison: shooting in a controlled environment, the Lathams' first projected films were of boxing matches, itself a form of theatre, while the Skladanowsky's films are records of circus or variety acts, as were many of Edison's films. With the appearance of new imaging technologies, their application is often confined by the uses of earlier forms. The technical superiority of the Lumières' system endowed the name of their technology to posterity and the institution of the cinema, but there is also a sense that the Lumières intuited the capacity of film for the contingencies of life from the outset. This may reflect the Lumières' backgrounds in photography itself, in contrast to Edison, the Lathams, and the Skladanowsky brothers.

the movement of inanimate objects excited a special interest: Of the many earliest written accounts of experiencing the first projected films by the Lumière brothers, most do not fail to mention the movement of the trees in the background of these films:

"The photographs I hear were taken at the rate of eighty to the minute, and, whilst the principle is not new, the representation of life-sized figures close to you, acting as human nature does act, the trivial and the significant all mixed up together, is totally new, and it is startling to see these congealed moments, as I may call them, suddenly become irrified at the turning of some Pygmalionic handle, the trees and bushes moving in the wind, the workpeople rushing out for dinner, mixed up with bicycles, carriages, dogs, and horses, you only miss the prattle and the argot."

‘Our London Letter’, The Star, St. Peter Port, Guernsey, 19 March 1896.

"But suddenly a strange flicker passes through the screen and the picture stirs to life. Carriages coming from somewhere in the perspective of the picture are moving straight at you, into the darkness in which you sit; somewhere from afar people appear and loom larger as they come closer to you; in the foreground children are playing with a dog, bicyclists tear along, and pedestrians cross the street picking their way among the carriages. All this moves, teems with life and, upon approaching the edge of the screen, vanishes somewhere beyond it.

And all this in strange silence where no rumble of the wheels is heard, no sound of footsteps or of speech. Nothing. Not a single note of the intricate symphony that always accompanies the movements of people. Noiselessly, the ashen-grey foliage of the trees sways in the wind..."

'Last night I was in the Kingdom of Shadows', ‘I.M. Pacatus’ (Maxim Gorky), Nizhegorodski listok, 4 July 1896.

"The Lumière Cinématographe will begin its fifteenth consecutive week at the Wonderland [Theatre] next week, continuing what was long ago the longest run ever made by any one attraction in this city. People go to see it again and again, for even the familiar views reveal some new feature with each successive exhibition. Take, for example, BABY’S BREAKFAST, shown last week and this. It represents Papa and Mamma fondly feeding the junior member of the household. So intent is the spectator usually in watching the proceedings of the happy trio at table that he fails to notice the pretty background of trees and shrubbery, whose waving branches indicate that a stiff breeze is blowing. So it is in each of the pictures shown; they are full of interesting little details that come out one by one when the same views are seen several times..."

The Post-Express, Rochester New York, 6 February 1897.

That animate bodies could be represented in movement was clearly understood as an extension of earlier optical toys: These 'optical toys', most famously the zoetrope, as well as the phénakisticope, praxinoscope, thaumatrope, and others, were not invented purely for amusement or entertainment: they were devices to demonstrate scientific principles. Their ultimate expression was, perhaps, in Émile Reynaud's

Théâtre Optique, which projected a succession of hand-drawn images on flexible film in 1892; these all paved the way for the technological means to conceive and reproduce a photographic moving image, but, importantly, also prepared its audience for the emergence of film as a medium, something early commentators explicitly noted:

“Our readers may probably remember the old “Wheel of Life,” [the zoetrope] and they are more likely still to be familiar with Edison’s kinetoscope. An instrument which is a further development of the principle of both these inventions is now on show in London, which is as far ahead of the kinetoscope as the kinetoscope was of the wheel of life. This is the cinematograph, which may be seen any day from 2 p.m. onwards at the Marlborough Rooms, in Regent Street.”

‘The Cinematograph’, The Sheffield & Rotherham Independent, 27 February 1896.

that exploited the perceptual basis of the moving image: The first descriptions of this perceptual basis are attributed to a paper presented to the Royal Society of London in 1824 by Peter Mark Roget, followed by the work of Joseph Plateau, the inventor of the phénakisticope, and that of Michael Faraday. Despite being superseded by the explanation of the

phi phenomenon for the perceptual basis of how a rapid succession of still images creates the impression of motion in the viewer, the colloquial concept of the 'persistence of vision' stubbornly remains.

The movement of the inanimate revealed something else, its archetype being the trace of wind in the leaves forming the background of a shot, returned to by many film makers since: In the Lumières' first public showing, as well as the animate, human subjects, the public would have also seen the movement of: water, under pressure, from a hose (

Le Jardinier or

l'Arroseur Arrosé); waves caused by wind (

La Mer or

Baignade en Mer); steam and smoke (

Les Forgerons); and the movement of leaves (most notably in

Repas de bébé, but also in

La Pêche aux poissons rouges, and

Le Jardinier to an extent). The famous train arriving at La Ciotat station featured in a later screening.

Film took photography’s capaciousness and extended this through the multiple image with the dimension of time: "Like photography, film tends to cover all material phenomena virtually within reach of the camera," Siegfried Kracauer,

Theory of Film. Kracauer's 'Inherent Affinities' in

Theory of Film are: the unstaged, the fortuitous, endlessness, the indeterminate, and the 'flow of life' ("peculiar to film alone," in which photography is extended by motion), all redolent of this capaciousness.

The lens renders anything within the frame with indifference:

"Here, then, is life; life it must be because a machine knows not how to invent; but it is life which you may only contemplate through a mechanical medium, life which eludes you in your daily pilgrimage. It is wondrous, even terrific; the smallest whiff of smoke goes upward in the picture; and a house falls to the ground without an echo. It is all true, and it is all false. [...] The newest toy attains this false reality without a struggle. Both the Cinematograph and the Pre-Raphaelite suffer from the same vice. The one and the other are incapable of selection; they grasp at every straw that comes in their way; they see the trivial and important, the near and the distant, with the same fecklessly impartial eye."

O. Winter, ‘The Cinematograph’, The New Review, May 1896.

its mechanical reproduction does not differentiate between its ostensible subject and that subject's surroundings: In comparison with the theatre, on stage, the background remains the background, the actors are in the same contiguous space as the audience, and, like the audience, separate from the set. In film, according to Béla Balázs, “...man and background are of the same stuff, both are mere pictures and hence no difference in the reality of man and object.” (Béla Balázs,

Theory of the film: character and growth of a new art).

Unable to control the viewer's gaze on the screen, the possibility of an open form arises: In practice, most films are constructed in such a way as to constrain the viewer's experience and attention, but the possibility remains that this gaze may be distracted by or come to rest on something other that the ostensible subject of the film, or, indeed the film-maker may explicitly design the disposition of the screen to provide a multiplication of points of interest, such as in Jacques Tati's

Playtime. The open form may also be achieved through narrative

irresolution.

A mark of the camera’s indifference was the revelation that film could disclose the life of objects: Perhaps most notable amongst many other examples, is the way silent comedy found a substitute for verbal wit in the wit of things: Chaplin’s boots, Harold Lloyd’s clock, Keaton struggling to stand upright in the wind, or trying to evade the boulders on a hillside chasing him. In these, the human figure is but one actor in the ‘flow of life’. One may also think of the last minutes of Antonioni's

L'Eclisse.

A screen of leaves becomes indicative of this life, a life clearly seen in its movement, an indexical sign of a force not visible: The imaginative screen of the first sentence has become the screen of leaves, filling the visual field, a screen which simultaneously shows and conceals, discloses and encloses:

"The drifting of clouds, the waves of the wind over a wheat field, the onrush of a waterfall, the swing of a pendulum, the up and down of pistons have lent more impact to many a film scene than all the gestures of the actors. This is not surprising for the actions of the inorganic world have a grandiose simplicity, which is not easily matched by the complex instrument of the human mind."

Rudolf Arnheim, 'Motion' in Film as Art.

***

Paper Cinema was shown in the

Documents exhibition at Lumen Studios in January this year.

The title, 'Paper Cinema', is borrowed from a chapter title in David Campany’s book,

Photography and the Cinema relating to printed work derived from, or aspiring to, cinema; the two prints and the attendant texts began as an idea for a short film with the text as a spoken narration heard while moving versions of the two still photographs appeared as successive split-screen images, the left image first, which would then be joined by the image on the right.

Both images were shot on 16mm black and white motion picture negative film stock. The text, which is, of course, also an image, made photographically, was shot on 35mm black and white document film. The photographic prints were made by exposing the paper to the negatives of the images and the text separately and successively in the darkroom before development.

***

Bibliography

Joseph and Barbara Anderson, 'Motion Perception in Motion Pictures', in The Cinematic Apparatus, edited by Teresa de Laurentis and Stephen Heath, MacMillan, London, 1980

Rudolf Arnheim, 'Motion' and ‘The Thoughts that Made the Picture Move’, in Film as Art, Faber, London 1958Bela Balázs, Theory of the film: character and growth of a new art, translated from the Hungarian by Edith Bone. New York, Dover Publications, 1970. Originally published 1952 by Dennis Dobson.

Stephen Barber, ‘The Skladanowsky Brothers: The Devil Knows’, Senses of Cinema, Issue 56, October 2010 http://sensesofcinema.com/2010/feature-articles/the-skladanowsky-brothers-the-devil-knows/ Retrieved 25/1/18.

Geoffrey Batchen, Burning with Desire: The Conception of Photography, MIT Press 1999

Phlip Brookman, Eadweard Muybridge, Tate Publishing, London 2010

Paul Burns, The History of the Discovery of Cinetmatography, http://www.precinemahistory.net/900.htm Retrieved 9/4/18.

David Campany, Photography and Cinema, Reaktion Books, London 2008

Alan Horder (editor), The Manual of Photography, Focal Press, London, sixth edition 1976 reprint.

Siegfried Kracauer, Nature of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality, Dobson Books, London, 1960

Written accounts of experiences of the first projected films are from the excellent Picturegoing blog. Italics added for emphasis in these accounts.