“The lights leap up, and at their sudden descent you see upon the cloth a factory at noon disgorging its inmates. Men and women jostle and laugh; a swift bicycle seizes the occasion of an empty space; a huge hound crosses the yard in placid content; you can catch the very changing expression of a mob happy in its release; you note the varying speed of the footsteps; not one of the smaller signs of human activity escapes you. And then, again, a sudden light, and recurring darkness.”

O. Winter, ‘The Cinematograph’, The New Review, May 1896

“Immediately after the command had been given to leave the factory back in 1895, the workers streamed out. Even if they sometimes got in each other's way - one young woman is seen to tug at another's skirt before they part in opposite directions, knowing that the other will not dare to retaliate under the stern eye of the camera - the overall movement remains swift and nobody is left behind. That this is the case is perhaps because the primary aim was to represent motion, maybe signposts were already being set. Only later, once it had been learned how filmic images grasp for ideas and are themselves seized by them, are we able to see in hindsight that the resolution of the workers' motion represents something, that the visible movement of people is standing in for the absent and invisible movement of goods, money, and ideas circulating in industry.

The basis for the chief stylistics of cinema was given in the first film sequence. Signs and symbols are not brought into the world, but taken from reality. It is as though the world itself wanted to tell us something.”

Harun Farocki, ‘Workers Leaving the Factory’

La Sortie de l'Usine Lumière à Lyon, known in English as

Workers Leaving The Lumière Factory in Lyon,

Employees Leaving the Lumière Factory, or simply

Exiting the Factory, was the first film to be projected in front of an audience, at the Société d'Encouragement de l'Industrie Nationale, on 22nd March 1895. It was the only film that Auguste and Louis Lumière then had available, and was shown, almost as an afterthought, following demonstrations of the Lumières’ experiments in colour photography. That this scene was chosen for the subject of their first film must be largely due to the pure, combined contingencies of proximity, of movement, and of light. The Cinématographe, fixed, unmoving, faces the entrance to the photographic plate factory in Lyon established by Antoine Lumière, Auguste and Louis’ father, and records the factory workers leaving through a large double gate and an adjacent doorway. The hand-cranked Cinématographe, a camera, printer, and projector combined in one device, was perhaps loaded that morning in the factory that ones sees in the shot; the film may well have been developed, and, now as a negative, dried, run back through the Cinématographe in contact with a fresh roll of film to make a positive print all in a day. Descriptions of

La Sortie de l'Usine Lumière à Lyon refer to it being “dinner hour”, “the noonhour at the factory”. Early film relied almost exclusively on daylight due to the limited sensitivity of the photographic emulsions available at the time, combined with the need for short exposure times in order to achieve sufficient successive frames with a fast enough shutter speed to create the impression of movement when played back. The noon hour outside the factory would provide the brightest intensity of available light during the day, and, additionally, the sun is behind the camera at that point in its path through the sky, ideal for defining the figures emerging into the street from the yard with the factory buildings behind (the factory entrances face south-south-west). Presumably, the first two contingent factors, of proximity and light, naturally suggested the third, movement:

“The Lumieres made several films of people filing past their camera, including one of workers leaving their factory, the first film to be screened publicly. The subject matter was ideal: endlessly different figures passing through a fixed frame express so much so simply, about photographs in motion.”

David Campany, Photography and Cinema

There are in fact three extant versions of

La Sortie de l'Usine Lumière à Lyon which suggests that the Lumières were sufficiently captivated by the subject to film it more than once, but perhaps also that they may have been unsatisfied with their first film itself. The version that Harun Farocki analyses in ‘Workers Leaving the Factory’ starts with the gates opening and ends with them closing, and appears the most organised visually (“In the Lumière film about leaving the factory, the building or area is a container, full at the beginning and emptied at the end. This satisfies the desire of the eye, which itself can be based on other desires.” Harun Farocki, ‘Workers Leaving the Factory’): the detail of one of the workers pinching the skirt of another before they part in different directions appears a knowing gesture, an improvisation or a deviation from the script which may itself suggest a familiarity to repetition. Farocki’s assertion that the worker whose skirt is tugged “will not dare to retaliate under the stern eye of the camera” is emblematic of the direction that these workers are subject to. The three different versions of the film are known by the presence - or absence - of a horse-drawn conveyance: it appears in two versions of the film, drawn by one horse in one, two horses in another, absent in the third. Farocki uses the ‘no horse’ version in his film

Workers Leaving the Factory; the figures streaming out of the factory gates, already open, in the one-horse film appear less organised than the ‘no horse’ version. The version of

La Sortie de l'Usine Lumière à Lyon was that was shown at the Société d'Encouragement de l'Industrie Nationale on 22nd March was filmed three days earlier on the 19th: in the one horse version, the shadow of bare branches can be seen on the ground, suggesting a date early in the year, as does the workers’ clothing - lighter clothes and bare arms are on show in the no-horse film and the shadow of the tree or trees behind the camera show that the leaves are out; all three variants were shot in sunlit conditions, and the visible shadows are relatively short, indicating a high angle of the sun in the sky, suggesting all three were filmed near midday. A more forensic analysis could no doubt place the time of day and year more precisely, given that the geographical location is known (the Institute Lumière reproduces the two-horse version on their

website as the Lumières’ first film; this version is more tightly framed, but the workers' clothing here again appears lighter than the one horse version).

Following the Lumieres’ first showing of projected films to a paying public on 28 December 1895 at the Salon Indien in the Grand Café, Paris, the Cinématographe was demonstrated to the public in London, at the Regent Street Polytechnic, on the 21st February 1896, with an invited audience the day before. The Polytechnic's own magazine reported the event as:

"a special exhibition of a new invention by MM. Auguste and Louis Lumière – the Cinématographe. [...] For instance, a photograph of a railway station is shown, two or three seconds elapse and a train steams into the station and stops, the carriage opens, the people get out and there is the usual hurrying for a second or two, and then again the train moves off. The whole thing is realistic, and is, as a matter of fact, an actual photograph."

The Polytechnic Magazine, 26 February 1896

The initial showing had a very small audience, fifty-four paying viewers, but, as in Paris, the Cinématographe's popularity, no doubt gained through press notices and word of mouth, soon required showings every hour on the hour between 2 and 10pm. Forty years later, the Regent Street Polytechnic marked the anniversary of this showing with a repeat of the original films and an exhibition, which situated the Cinématographe amongst other technologies creating the illusion of the moving image, the phenakisticope, zoetrope, Edison's Kinetoscope, and was opened by Louis Lumière himself. 'The Lumière Celebration' programme reproduces the original list of films shown in February 1896:

La Sortie de l'Usine Lumière à Lyon is not listed; however, tantalisingly, there is a sentence that reads that the programme "will be selected from the following subjects, and will be liable to frequent changes, as well as ADDITIONAL POURTRAYALS [sic]".

The Lumière's Cinématographe used 35mm-wide film, but, unlike Edison's Kinetoscope, which essentially introduced the form of 35mm perforated film still in use today, this used a single round perforation per frame on each side. Smaller formats were soon developed for amateurs: Kodak developed 16mm film, and, a few years later, repurposed it by doubling the number of perforations, and created the 2x8mm format which was popular for home movies until Kodak produced the Super-8 cartridge which all but made 2x8mm obsolete. Despite its near-obsolence, I have used 2x8mm film in recent years; in experimenting with a Bolex 8mm camera, I discovered that unperforated 16mm film would run through it. I had tried some single-perforated 16mm

Double-X film, to test exposure and development of that particular film with the camera. The perforated side ran through the Bolex with the frames overlapping in pairs, a result of the 16mm film having half the number of perforations of 2x8mm film. Having shot the perforated side, I turned over the film and tried shooting the unperforated side - which worked. As I had a length of

Ilford FP4 Plus film cut down to 16mm, I tested this to see if I could shoot it with the Bolex camera, and it worked. With the #FP4Party returning this March, in my desire to do something different for it, I thought that I could actually make a short film shooting on Ilford FP4 Plus itself (coincidentally, when Ilford used to make ciné film many years ago, FP4 was one of the emulsions supplied in 16mm). Searching for a subject, I was provoked by seeing images of the location of Ilford's Britannia Works site on social media promoting this month's #FP4Party; these were of course familiar, as in 2013 I'd spent some time researching the Ilford company's beginnings in Ilford,

writing a long post about this, illustrating it with photographs shot on

Ilford document film with an

Ilford camera.

|

| Bolex test with unperforated Ilford FP4 Plus |

Cutting medium format film to 16mm wide meant that duration would be fixed by its length. 120 rollfilm is about 82cm long; 2x8mm film has 80 frames per foot, meaning I could get something less than 240 frames per side on a cut-down section of film - not including losing a little of the length threading the film through the camera gate and on to the take up spool. The Bolex B8 has a wide range of filming speeds, so I was not constrained to shooting at the standard silent speed of 16fps, which would give just ten seconds of running time per side. To increase the duration of the film, I cut three lengths of medium format FP4 Plus, and taped these together in the dark; ideally, I wanted the film to be the same duration as those first Lumière films, which had a maximum running time of 50 seconds, taking 17 metres of 35mm film; shooting at 12fps, I thought it would be possible to shoot around 45 seconds on three lengths of cut-down FP4 Plus joined together. This also required loading, then opening the camera after shooting the first side to turn the film over, and finally unloading it all in the dark, to make use of as much of the film as possible. I took a changing bag with me to turn the film over on location after having shot the first side.

In my research into the Britannia Works site, I wrote briefly about my personal connection to Ilford, having grown up there, with my family moving to the town just before all the buildings on the Ilford site were demolished; we tended not to use the Sainsbury's supermarket that was subsequently built there at the time, but in the mid-1990s my brother bought his first house in a post-war estate at the far end of Riverdene Road from it. Away from London studying during this period, and after finishing my degree, I would stay there on occasion, as a result making it very familiar, but also associated with a particular period in my life. I think we may have also visited the Papermakers Arms pub on the corner of Roden Street and Riverdene Road once or twice, but around that time there were a number of pubs in the town that I only visited once or twice. I certainly went to the Cranbrook, a pub on the site of Alfred Harman’s home where he began making ‘Britannia’ dry plates in 1879, starting the business which was to become Ilford Limited.

As the FP4 film loaded into the Bolex, even with three lengths joined together, provided a short duration, I wanted a simple subject, one single fixed shot for each side of the film. I planned to film the locations where entrances and exits to Britannia Works, a factory manufacturing photographic plates like the Lumières', used to be, 125 years on from their first film. Changes to Ilford's Britannia Works site took place in 1896, the year the Cinématographe was exhibited in London, extending it to Roden Street, part of the current road layout. Revisiting the site this year in early March, around the corner on Riverdene Road, the two dilapidated houses next to the Papermakers Arms have gone since my post of 2013; these were demolished four years ago, and a new building is currently going up on their footprint. On Roden Street, opposite Sainsbury's, an area which also had some Ilford premises, Britannia Music Publishing had their headquarters, one of the few high rise developments while I was growing up in Ilford. In 2013, this too had been demolished and the site cleared, now populated with tall buildings in the process of being completed, typifying how land use has changed in the last decade or so.

|

| Roden Street/Rollei 16 with Ilford FP4, develop before July 1975 |

I set up my camera opposite the exit to Sainsbury’s car park for the first shot. Before the changes to Britannia Works in 1896, the site boundary would have been roughly in the position of the ramp over the exit. I felt certain that the exit to car park itself would provide movement as I filmed: indeed, there was a worker painting the bollards between the way in and way out lanes as I set up the tripod. All around me, there was work going on as I filmed. Behind the camera, the understory car park beneath the new development was being surfaced with tarmac. In front, but just out of view of the lens, the pavement had been dug up and a lorry parked alongside. Two construction workers crossed the road behind this out-of-shot lorry as I filmed.

|

| Riverdene Road/Rollei 16 with Ilford FP4, develop before July 1975 |

The second shot is of a narrow section of brick wall, projecting from the south-western corner of Sainsbury’s car park. In my research of 2013, I had identified this as fitting the size and position of an entrance to the alley that led to Britannia Works before the site was extended to Roden Street in 1896. As a subject, the blank brick wall is antithetical to the idea of “photographs in motion” and it looked as though there would be no movement at all when I began filming, perhaps appropriate to shooting what

used to be an entrance but is no longer. The camera jammed as I filmed this. Opening it in the changing bag, one of the taped joins between two of the cut lengths of film was in the gate, and I moved this through manually. Continuing to film, a car and a pedestrian passed along Riverdene Road before the film ran out.

|

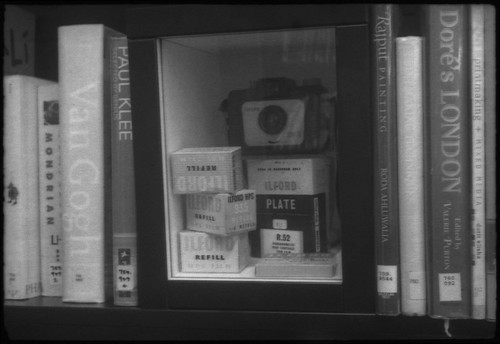

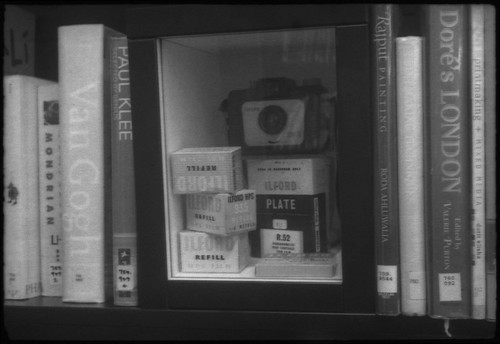

| Rollei Super 16 cassettes loaded with Ilford FP4 film with a develop before date of July 1975 |

I also shot still photographs on Ilford FP4 with a “develop before” date of July 1975, the previous iteration of Ilford’s ‘Fine Grain Panchromatic’ film before the ‘Plus’ suffix was added. This FP4 is single perforated 16mm film, ready-loaded into 'Super 16' cassettes for the

Rollei 16 subminiature camera. The film boxes state that the film is “Packed by Rollei-Werke Franke & Heidecke Braunschwieg Germany”. It’s entirely possible that this film itself was manufactured on the Roden Street site before the factory closed. The last photographic plates were coated there in November 1975; given that develop before dates are usually a few years from the point of manufacture, this FP4 film was possibly made around 1970, soon after FP4 film supplanted FP3. The 16mm film does not possess ciné film edge markings, but has frame numbering for the 12x17mm Rollei 16 format, as well as the stylised ‘R’ from the Rollei typeface. I did briefly consider using this film in the Bolex, but the Rollei cassettes only contain approximately 50cm of film, much shorter than the cut-down medium format FP4. In addition, the tests I’d previously made demonstrated that with standard 16mm perforations the frames would overlap on the perforated side, which would be hardly ideal.

|

| Ilford Sprite camera in Redbridge Central Library/Rollei 16 with Ilford FP4, develop before July 1975 |

After shooting the film and taking some still photographs, I went to Redbridge Central Library, where I’d conducted my research in the local studies section seven years ago. There, in the non-fiction section, I photographed the small display case containing an Ilford Sprite camera, a box of R.52 Panchromatic plates and rolls of 35mm HPS film refills. The local studies section has been reorganised since I was there last (the museum itself appeared unchanged, with its case about Mary Davis, who worked at Ilford until it closed in 1976); upstairs there was a display about the various resources available to research local history, including a section on the 1911 census. This highlighted a family who lived in Margaret Cottages, the houses demolished four years ago next to the Papermakers Arms, and this included a photograph from 1984 I hadn't seen before of Riverdene Road with Margaret Cottages being overshadowed by the Ilford factory, of which I made a thumbnail sketch.

The raised steps outside the doors of Margaret Cottages, something I’d noticed as being distinctive, indicated that the whole ground floor of the houses was raised to protect the properties from flooding by the nearby river Roding, with one notable flood occurring in June 1903, and another more recent one in 2000. Earlier in the day I had got down to the Roding at the end of Roden Street, between the flats built there, a development from a few years back now; I imagine this is all private land, but there was nothing to stop me getting alongside the railings bounding the river (on the other side, the A406 road essentially prevents access to the river for a long stretch). I had found a reference in

Silver by the Ton to glass plates being dried in the open air by the river (presumably after cutting and cleaning, before coating); this stretch of the Roding also used to be known as the Hyle, from which Ilford is derived.

|

| The Roding by Roden Street/Rollei 16 with Ilford FP4, develop before July 1975 |

I developed the FP4 Plus from the Bolex with D96; as there were three lengths, I developed one first, separated from the others, removing the tape from the joins so that these areas would also develop. The first length appeared thin, due to the D96 being close to exhaustion, so I increased the developing time of the second two, almost doubling it (the first length of film I’d developed for 10 minutes at 21ºC, the second for 18 minutes at the same temperature). One of these came out entirely blank, which must have been from the taped join here also getting stuck in the gate, and I had turned the film over in the camera at this point between exposing the first and second sides: out of two runs through the Bolex camera, only one taped join passed through the gate in one direction without getting stuck. I had tested this beforehand, but without doing this in the dark: it’s much easier to neatly tape a couple of lengths of film together when you can see what you’re doing. Once developed, it was clear that the frame spacing was more erratic than the previous test I had made on unperforated film, although the total running time would have been close to

La Sortie de l'Usine Lumière à Lyon if all three lengths of film had gone through the gate. The still images were developed in Ilfotec LC29 at a dilution of 1+19, and I had rated the film at an exposure index of 40, which gave rather dense negatives.

|

| Inverted negative showing irregular frame spacing |

“The first camera in the history of cinema was pointed at a factory, but a century later it can be said that film is hardly drawn to the factory and is even repelled by it. Films about work or workers have not become one of the main genres, and the space in front of the factory has remained on the sidelines.”

Harun Farocki, ‘Workers Leaving the Factory’

Harun Farocki’s film

Arbeiter verlassen die Fabrik (

Workers Leaving the Factory) was made in 1995, the centenary of the Lumières’ first films, of which there was revival of interest, notably with the compilation film,

Lumière et compagnie; Farocki’s film is a collage of cinema’s originary motif, culled from documentaries and features (“I have gathered, compared, and studied these and many other images which use the motif of the first film in the history of cinema, "workers leaving the factory," and have assembled them into a film”). In doing so it would appear that this film itself reanimated the subject, with the caveat that this is largely in the realm of the non-fiction film:

“In recent years, a number of remakes of the Lumière Brothers’ Workers Leaving the Factory have appeared. This particular Lumière film has become a touchstone for filmmakers in the past two decades, beginning with Farocki’s Workers Leaving the Factory, which compiles footage of workers exiting factories from many different fiction and nonfiction films, drawing our attention to how frequent and yet parenthetical or unexplored this visual image is in film history.”

Jennifer L Peterson, 'Workers Leaving the Factory: Witnessing Labor in the Digital Age'

Peterson’s prime examples are Ben Russell’s

Workers Leaving the Factory (Dubai) from 2008, which clearly references the Lumières' film in its title and form, being a single long take of migrant workers leaving a construction site; Sharon Lockhart’s

Exit (also 2008) which reverses the viewpoint of

La Sortie de l'Usine Lumière à Lyon by placing the camera inside the factory gates looking out, filming the workers leaving an iron works on five successive weekdays in five unedited shots; and Daniel Eisenberg’s

The Unstable Object (2011), which contrasts three different factories, from a technologically advanced car factory, to handmade clocks by visually impaired workers, and the traditional casting and finishing of cymbals. Referencing David Harvey, the theme of uneven geographical development is touched upon, especially in the contrasts in Eisenberg’s film, but also with the use of migrant labour in Russell’s

Workers Leaving the Factory (Dubai); Lockhart’s

Exit pictures a form of labour, once familiar to many, but increasingly outsourced from the global north.

“The title of the first film by the Lumière brothers (La sortie des usines, 1895) also prophetically describes the changes in working conditions that took place in the twentieth century.”

Volker Pantenburg, ‘Deviation as Norm—Notes on the Essay Film’

The site bounded by Roden Street and Riverdene Road can be taken as emblematic of changes from the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 21st. Ilford’s Britannia Works did not start as a greenfield site, but literally as a cottage industry, expanding from Alfred Harman’s home to a rented cottage on the Clyde Estate and from there growing quickly during the very end of the 19th century into the beginning of the 20th. The factory incorporated social functions, with clubs, newsletters and such like, as evidenced by Mary Davis’ comments in the local museum. Without unnecessarily fetishising the solidarity of this form of labour, much of these functions have disappeared in the post-war decades. At the end of the 1970s, Ilford Limited moved away to Cheshire, and its other sites in Basildon and Brentwood were closed, consolidating production. The closure of Britannia Works in Ilford made possible the redevelopment of the town centre, the road scheme surrounding the site reflecting the increasing dominance of the private car in the 1980s, and the site moved from being one of production to a site of consumption with the arrival of the supermarket.

The title

Workers Not Leaving The Factory alludes to two versions of ‘not leaving’: first, this is the site where a factory was, but is no longer, a simple temporal dislocation. At the time the Lumières demonstrated the Cinématographe in London, there would have been workers leaving the site each day (I could have waited until the supermarket closed at the end of the working day, but at 10pm, there wouldn’t have been enough light to film; I shot at lunchtime, appropriately, and the working patterns in grocery shops certainly do not include closing for lunch: in the shot on Roden Street shoppers are seen leaving the supermarket). Second, for many occupations, although not those physical, repetitious ones which typically take place in factories or on construction sites, obliquely seen in the film, work in the 21st century is never truly left behind when one exits the premises: the site of work is all pervasive in the digital realm. Of this kind of work, if 'the factory' stands in for work itself, then work is all around in a sense that the workers leaving the Lumière factory could never have conceived: once they had left the factory site, work had no call on them until they reappeared for their next shift.

Bibliography

All three versions of La Sortie de l'Usine Lumière à Lyon are on YouTube here.

The Regent Street Polytechnic Lumière Celebration programme (PDF) http://www.cineressources.net/ (retrieved 12/03/20)

David Campany, Photography and Cinema, Reaktion Books, London 2008 (2012 reprint)

Harun Farocki, Imprint/Writings, (English translation by Laurent Faasch-Ibrahim) Lukas & Sternberg, New York, 2001

Harun Farocki, Arbeiter verlassen die Fabrik (Workers leaving the factory), 1995 https://vimeo.com/59338090

David Harvey, Spaces of Global Capitalism: Towards a Theory of Uneven Geographical Development, Verso, London, 2006

RJ Hercock and GA Jones, Silver by the Ton - A History of Ilford Limited 1879-1979, McGraw-Hill, London, 1979

Joost Hunningher, 'Now showing at 309 Regent Street – Ghosts on ‘Our Magic Screen’. A screenplay' in The Magic Screen, Joost Hunningher, Rikki Morgan-Tamosunas, Guy Osborn and Ro Spankie, University of Westminster Press, 2015

Sharon Lockhart, Exit, 2008. Available online at www.ubu.com/film/lockhart_exit.html

Volker Pantenberg, ‘Deviation as Norm—Notes on the Essay Film’ in Farocki/Godard, Amsterdam University Press, 2015 (https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt16d69tz.7 retrieved 21/2/20)

Jennifer L Peterson, ‘Workers Leaving the Factory: Witnessing Labor in the Digital Age’, The Oxford Handbook of Sound and Image in Digital Media, 2013 (https://www.academia.edu/5728999/Workers_Leaving_the_Factory_Witnessing_Labor_in_the_Digital_Age retrieved 1/3/20)

Ben Russell, Workers Leaving the Factory (Dubai), (2008) Available online at http://vimeo.com/7528954

Ro Spankie, ‘The ‘Old Cinema’: a dissolving view’ in The Magic Screen, Joost Hunningher, Rikki Morgan-Tamosunas, Guy Osborn and Ro Spankie, University of Westminster Press, 2015O. Winter, ‘The Cinematograph’, The New Review, May 1896 (https://picturegoing.com/?p=4166 retrieved 21/3/20)