|

| Pentax Auto 110 with 24mm lens |

The

Pentax Auto 110 is a remarkable single lens reflex camera on a miniature scale for the

110 format. Although the subminiature format was popular with many other Japanese manufacturers from the adoption of 16mm film for still picture cameras in the 1950s, through to the introduction of the 110 cartridge in the 1970s, Asahi/Pentax only entered the subminiature market with the Auto 110 in 1978. However, the Pentax Auto 110 was not the first SLR for the format: two years earlier, Minolta had produced their initial model of the

Minolta 110 Zoom SLR. The Minolta cameras had a fixed zoom lens with aperture priority exposure and a range of ISO settings; by contrast, the Pentax was far more compact, measuring just 98x56x43mm with the 24mm lens, yet it has interchangeable lenses, fully automatic exposure, and a range of accessories.

As an SLR system camera, designated by Asahi simply as '

System 10', the Pentax Auto 110 was provided with a full range of lenses: as standard, the 24mm lens represents the 'normal' angle of view, and was complemented with the 18mm wide angle, 50mm 'portrait' lens, 70mm telephoto and 20-40mm zoom. Focus on all lenses except the fixed 'pan-focus' version of the 18mm is manual: the viewfinder has a split image central spot. As the unique two-bladed diaphragm combines both shutter and aperture and is an integral part of the camera body (shown in the image below), all lenses had to work with the same maximum aperture of f2.8, which stops down to the smallest aperture of f13.5 in the right conditions. There was also a third-party 1.7x teleconverter from Soligor, and a

number of filters for the different lenses, including UV and skylight, but also close-up

fliters. Other accessories include two different flash units, a power winder, and a belt clip.

|

| Pentax Auto 110 with lens removed |

As the name suggests, the TTL exposure is entirely automatic: lightly pressing on the shutter button, an LED shows in the bottom right corner of the viewfinder, green for shutter speeds above 1/30th, yellow (for low-light) speeds below 1/30th. Exposures ranged from 1 second at f2.8 to 1/750th at f13.5. The Pentax Auto 110 does use the 110 cartridge's film speed tab to set exposure at either 80 or 400 ISO (some websites list the high speed setting as 320 ISO). As exposure is automatic, it's important to note that the camera does not work without batteries: the SLR mirror does flip up mechanically, but the shutter itself will not fire. Fortunately, the camera utilises two SR44/LR44 type batteries which are commonly available. The removable battery holder has a unique design with rotational symmetry which means it works inserted into the camera either way up.

|

| Pentax Auto 110 with open back & battery holder removed |

The Pentax Auto 110 in the images illustrating this post was left behind when a family member emigrated, and had evidently not been used for some time when I chanced upon it. Opening up the camera revealed two heavily furred batteries, but after cleaning the battery compartment and the contacts, I inserted two new batteries, and the light inside the viewfinder came on when lightly depressing the shutter button. The battery compartment also had some damage, where the plastic edge seperating the film chamber from the batteries had broken away, which may have been due to leaking battery acid. This does not appear to affect performance directly, but, as I later found, it may have meant that the batteries fit less securely. I very quickly found a 50mm lens online to supplement the 24mm, for just £7, so ordered this and a couple of film cartridges.

|

| Pentax Auto 110 with 50mm lens |

In a number of my posts about 16mm subminiature cameras, I have referenced the 110 format as a point of comparison. Kodak introduced the 'pocket instamatic' drop-in cartridge in 1972, essentially a smaller version of the earlier 126 cartridge, which succesfully competed with the various 16mm subminiature systems, and the format was very popular through the 1970s and into the 1980s. As a format commonly used for cheap snapshot cameras, like 126 and the short lived

APS film, the 110 film cartridge was a casaulty of digital photography, and most companies had discontinued production by the mid-2000s, the last being in 2007, but since 2011 the format has been ressurrected with Lomography marketing both colour and black and white 110 films. The first production run of Lomography's black and white 'Orca' film cartridge didn't use backing paper, but subsequent batches do, which is useful to have when reloading the cartridge.

I bought a cartridge of the Lomography Orca film to test the Pentax Auto 110. After loading, I shot a few frames before realising that the exposure LED was not lit. This turned out to be poor battery contact, perhaps caused by the damage to the battery compartment. I removed the film cartridge (although later realised this could be done with it in place), and wedged a small piece of folded card to force the metal

contacts tighter to the batteries. I also shot an old

Kodak Verichrome Pan cartridge (with a develop before date of Sept 1978), this being the only black and white film originally made for the 110 format - until

Lomography's reintroduction in 2011. This cartridge contained 12 frames, and due to the camera's fully automatic exposure, I was unable to compensate for the age of the film when shooting. I attempted to do so when developing, but with

little success. Lomography's website has

times for a number of film developers, but using the unlisted Ilfotec LC29, I choose to utilise stand development at a dilution of 1:100, for one hour with the Orca film, and two hours for the Verichrome Pan.

|

| Lomography Orca 110 format film |

One of the first things I noticed after developing and scanning the films was the clear presence of an overlap around the printed frames. This can be seen in the scan below, particularly in the lights around the top and sides of the frame. Kodak's original specifications for 110 film included this pre-exposed frame for the convenience of photo-lab printing. It was interesting to discover that the printed frames were not insignificantly smaller than the actual frame size that the camera uses. I attempted to measure the size of the pre-exposed frames from the scanned negatives, and got the following approximate measurements: Kodak's Verichrome Pan frames were 12.6x16.9mm; the Lomography Orca frames were practically the same at 12.7x17mm. However, without the pre-exposed frame, the Pentax Auto 110 has a negative size of 13.4x19.6mm. At the small scale of the 110 format negative, the extra 2mm width is not inconsiderate. In terms of area, the Orca negative is 215.9mm

2, compared to 262.6mm

2 without the frame, a difference of 21.6 per cent.

|

| Orca 110 film, showing overlap with printed frame |

Unlike the cassettes of the 16mm subminiature cameras I've used recently, the 110 cartridge is not designed to be reloaded with film and re-used. This I think represents something of a split between the formats, as, although the various different 16mm cassettes could be bought ready loaded with film, these cassettes were designed to be reloaded by the user - for example, my

Kiev-30M box set came with two empty cassettes. The 110 cartridge is made to be used once, and handed in to be professionally processed. Although it may be fanciful to characterise this split as that between a consumer and an

amateur, implying more the original sense of the word, reloading and reusing 16mm subminiature cassettes requires a certain level of commitment from the user, different from the spirit of the single-use drop-in cartridge. Additionally, the pre-exposed frames of the 110 format also impose limitations on camera manufacturers: by comparison, although there is a standard 35mm frame size, there are cameras which use different format frames, such as half frame, or the few odd cameras which take square format images. Likewise, 120 rollfilm cameras use 6x9, 6x7, 6x6, 6x4.5 framings, among others. 16mm subminiature cameras also had different frame sizes: generally, as the cameras were developed, frame sizes expanded, from cameras designed with frame sizes to fit between the holes of double-perforation film, to larger areas using nearly the full width of unperforated film. There was even a 16mm panoramic camera: the

Viscawide-16.

|

| Pentax Auto 110 with 24mm lens, cartridge reloaded with Kodak WL Surveillance film 2210 |

Having used two 110 cartridges and developed the films, the next step was to reload them. The website Instructables has

a good guide to taking apart and reloading a 110 cartridge, which I looked at before my own attempts. The Orca cartridge came apart relatively easy after scoring the seams at each end and around the two chambers. The Kodak cartridge seemed more securely put together, and broke, although with each chamber intact, it could still be reloaded, and held together with more tape. There are some issues with reloading 110 cartridge with 16mm film. Ideally, unperforated film should be used, but the only unperforated film I currently have, Agfa Copex HDP 13, is too slow to be used in the Pentax Auto 110. I used

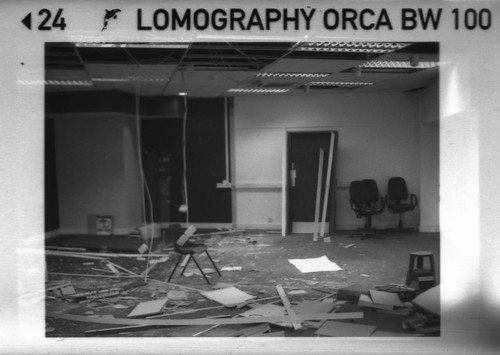

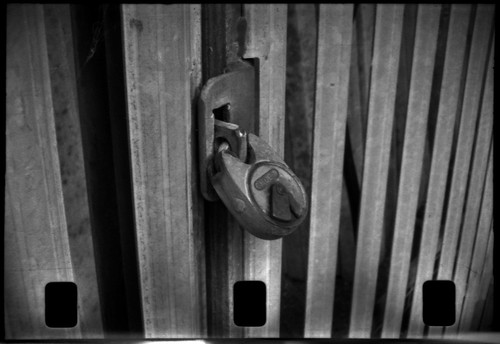

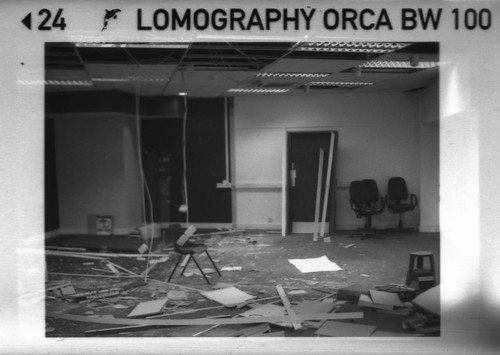

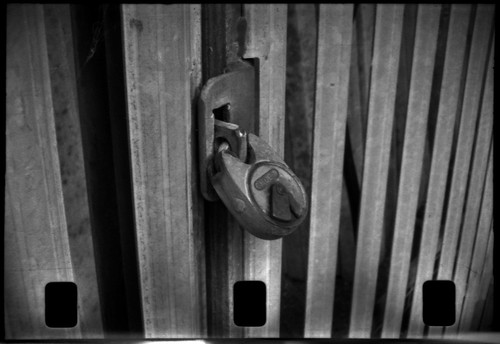

Kodak WL Surveillance film, single perforated, with the perforations at the top of the cartridge, meaning that these would be at the lower edge of the frame. This also ensured that the pin to register 110's single perforation for each frame is not confused by the perforations along the edge of the 16mm film. This pin is used by the camera to stop film advance for each new frame, released when the shutter button is pressed. In some cameras, this pin is also used to cock the shutter, but this is not the case with the Pentax, where the shutter is cocked on the second stroke of its two stroke film advance. Without a perforation to register each frame, it is possible to shoot frames against the leader and trailer of the film's backing paper, providing that there is enough overlap of film, and it is also possible to wind the film through the camera without shooting a frame, as film advance doesn't stop on each unxposed frame. Additionally, some of the frames once developed show surge marks around the perforation holes, visible in the shot of the padlock further below.

|

| Pentax Auto 110 with 50mm lens, Kodak WL Surveillance film 2210 |

|

| Pentax Auto 110 with 50mm lens, Kodak WL Surveillance film 2210 |

I modified the Orca cassette to use it for high speed film by

cutting down the tab, as I had been shooting the Kodak WL Surveillance film at EI400. For this first reloaded roll, I used stand development with Ilfotec LC29, diluted 1:100 for one hour. The test roll negatives looked dense, which suggested overexposure, but this may have been mitigated by the effects of stand development and the WL Surveillance's good latitude. Subsequent scans from the film above show a good tonal range, without blocking in the highlights. To check for a difference in exposure though, I shot another two rolls of reloaded Kodak WL Surveillance film, one

in the unmodified Verichrome Pan cartridge, the other in the Orca cartridge, which should have meant that the camera would rate the VP cartridge at 80, the Orca at 400. Both films were stand developed (together) in Ilfotec LC29, with dilution increased to 1:150, and a slightly shorter time of 50 minutes. Both sets of negatives (shown immediately below) looked as though they had recieved the same exposure. As the Pentax Auto 110 does have the high speed/low speed switch, I concluded that this wasn't working, and both films were rated at 100. I may not have cut the film speed tab correctly, or perhaps, as the film speed switch is next to the battery compartment, its connections may have been damaged by leaking battery acid. Regardless, the WL Surveillance film worked well enough automatically exposed by the camera, and when I shot more reloaded cartridges, I used stand development at 1:100 again, for one hour.

|

| Kodak WL Surveillance film, stand developed in Ilfotec LC29, 1:150 |

|

| Kodak WL Surveillance film, stand developed in Ilfotec LC29, 1:150 |

The limitations of the Pentax Auto 110 are essentially the limitations of the

original 110 format specifications. With fully automatic exposure, it can only be used with films close to the two ISO settings, but as Lomography's currently available films are 100 and 200 ISO, this is only an issue when reloading cartridges For films of slower (or faster) speeds, development could be tailored to

compensate for over or under exposure, but the use of much slower films with finer grain may not be advisable due to the effective push increasing contrast. There was a second version of the camera, introduced in 1983, the

Pentax Auto 110 Super, which had a number of improvements, such as a single stroke advance lever, backlight compensation, self-timer, a shutter lock and a smaller minimum aperture. However, the Super was produced in much smaller numbers, as the popularity of the 110 format was already waning in the mid-1980s. Now 110 films are available once again, the Pentax Auto 110 SLR must be one of the best secondhand cameras around for the format.

|

| Pentax Auto 110 with 24mm lens, Kodak WL Surveillance film 2210 |

|

| Pentax Auto 110 with 24mm lens, Kodak WL Surveillance film 2210 |

|

| Pentax Auto 110 with 50mm lens, Kodak WL Surveillance film 2210 |

Sources/further reading:

http://www.pentax110.co.uk/

http://www.photoethnography.com/ClassicCameras/AsahiPentaxAuto110.html

http://www.cameraquest.com/pentx110.htm

110 Format:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/110_film

http://www.lomography.com/magazine/lifestyle/2012/06/18/the-demise-and-comeback-of-110-film

http://www.frugalphotographer.com/info-110.htm