|

| Kodak No.2A Brownie |

In the early years of photography, most negatives were printed by contact, which in turn, helped to define the size and design of cameras. This was essentially true with the burgeoning popularity of amateur photography at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. Kodak definitively helped in this by producing extremely low-cost cameras, embodied by the Brownie range of box cameras. As the range expanded, cameras were made for larger image formats: the

Kodak No.2A Brownie was introduced in 1907, and took 116 rollfilm, with a nominal negative size of 6.5x11cm (2½ x 4¼ inch). The original Brownie and the No.2 Brownie both had new rollfilm formats (117 and 120), with the same negative dimensions, 2¼ x 3¼ inch, but on different spools. For the larger negative size of the No.2A Brownie, the camera was designed to use the existing

116 film, which had been introduced a couple of years prior to the first Brownie camera, in 1899. As a result of the negative size, format and focal length, the No.2A Brownie is a moderately large box camera, measuring 13x8.5x15.5cm.

|

| No.2 Brownie (front) with No.2A Brownie (rear) |

Although it uses a different film format, the No.2A Brownie's specifications are very similar to the No.2 Brownie, which may be why it was named thus (and most of the

detailed post I wrote about the No.2 Brownie could equally be applied to the No.2A); a No.3 Brownie followed in 1911 for 124 rollfilm, and a No.2C in 1917 for 130 film, both with larger negative sizes again (there wasn't a No.2B, a construction that Kodak appears not to have used for any of their cameras; the 'A' suffix is used for most 116 cameras, although not exclusively, while the 'C' was used for 130 film; following the success of the

Vest Pocket Kodak, there was also a No.0 Brownie for the smaller format

127 film).

The original price for the No.2A Brownie was $3.00 (the No.2 was $2 when it was first marketed), and it seems that initially, at least, it

shared a manual with the No.2 Brownie, although subsequently

a manual for both the No.2A and the No.3, after the latter camera was produced. Thus, using the No.2A Brownie, apart from the film size, is the same as the No.2 Brownie: the rotary shutter has a single speed of around 1/30th and trips in both directions, while pulling a tab on the left above the lens provides a time setting for long exposures; there are three apertures punched in a metal strip that can be pulled into position using the central tab above the lens, approximately f11, f16, f22, but most likely non-standard, if the measurements I made for my No.2 Brownie's apertures were at all accurate; film advance is manual of course, using the bar winder with a red window for frame numbers; the vertical and horizontal reflecting viewfinders, although small and not very distinct, give a fair idea of composition. One difference between my No.2 Brownie, and the No. 2A is that the cardboard-bodied Brownie cameras do not have tripod fittings, unlike the later metal ones.

My version of the No.2A Brownie is the Model B, introduced in 1911, although, as I wrote in my post for this year's

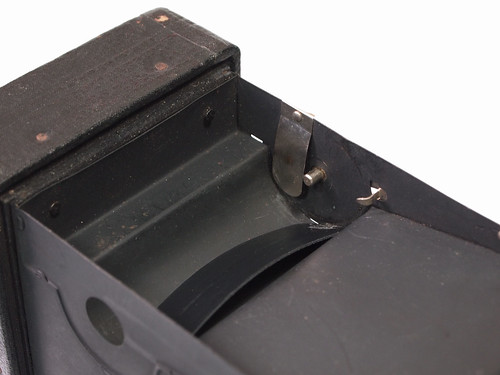

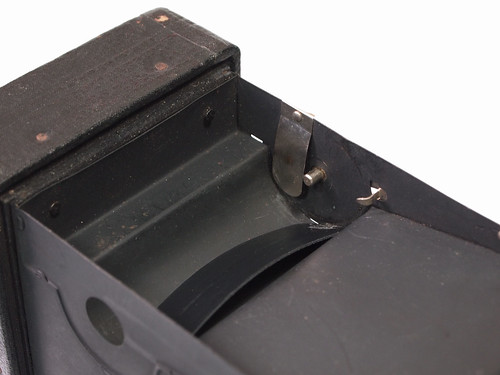

Take Your Box Camera To Work Day, details of the camera itself securely date its manufacture to some time between June and October 1917. On the

Brownie Camera Page, the list of variations gives the following information- "June 1917: Film tension springs were moved from the center to the spool ends. Oct 1917: The case latches were improved with rounded ends and milled edges." My version of the No.2A Brownie does have what I would describe as the 'spool-end tension springs' (as can be seen in the images below), but the case latches have unmilled ends (this milling was a fine serration around the edge of the latch to improve grip).

|

| Kodak No.2A Brownie with back removed for loading |

The cardboard body model loads by removing the entire back. In the image above, a 120 spool with adaptors to fit 116 can be just seen in the supply side film chamber; the round hole at the bottom is for the winding key to be inserted into the take up spool end. The interior film carrier is made of metal. My version has a set of patent dates embossed in the metal; the patent for April 11 1899 must be for 116 film itself; with the other two dates, it's less obvious what these might relate to. In the early years of camera manufacture, Kodak was very liberal with prominently placing its patent dates all over its products, but generally these can't be used to date the cameras too securely.

|

| Spring tension |

One minor modification I made to my No.2A Brownie was to insert a piece of thin plastic sheet slightly wider than the take-up spool chamber to act as an additional pressure plate to ensure that the take-up spool is tightly wound. I added this specifically for 120 film, which is smaller in diameter than the original 116 spool that would be used in the camera, but kept it in the camera when I did use an old roll of 116 without any detrimental effect. When researching the Kodak Brownie 2A, I noted that the price list in the back of the manual lists two films for the No.2A - for six exposures or twelve exposures; later, 116 film was only available with eight exposures (similarly, 120 film was originally provided in six exposure lengths rather than eight). It's notable that in eight exposure rolls, the metal 116 spool ends are clearly wider than the diameter of film and backing paper; twelve exposure rolls would no doubt have much less of a gap.

|

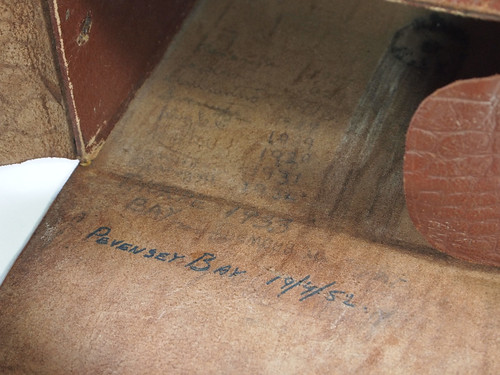

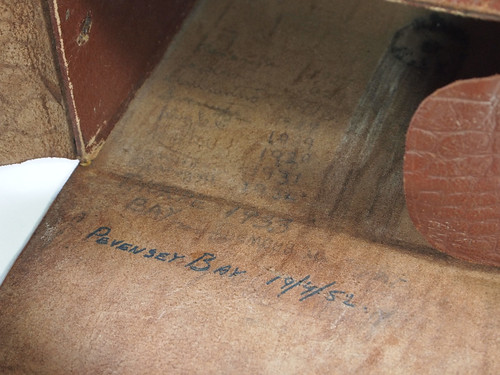

| Kodak No.2A Brownie case with dates and locations |

Inside the crocodile-skin-effect case, a previous owner has written a list of places with dates, covering a span of 25 years, from 1927 to 1952 (with a large gap from the penultimate date of 1933 and the last in 1952; this final name is also in pen while the rest are in pencil, but it does appear to be the same handwriting). The camera was already ten years old at the beginning of the this list, although the reasons for this may be many and various; the camera may have been secondhand and imported, as all the locations are in England and Wales, yet the camera was made in America according to the details on the

Brownie Camera Page. Although the No.2A Brownie was produced in UK from 1930-36, this was the later Model C version, with an aluminium rather than cardboard body, with a number of other refinements.

For a first test of the No.2A, I shot some Fomapan 200 using the

adaptors that I had previously made to fit 120 film into 116 format cameras. When I developed the film, there were two clear problems: numerous scratches all along the film, but also there were light leaks from the red window along one edge of the negatives. The scratches were clearly from the rollers inside the camera, which I gave a good clean, although this did not entirely eliminate this problem, as was evident in later shots. The image below also shows a slight overlap of negatives on the right hand side where I did not get the frame spacing quite right. However, the first test roll did show that the size of the negative provided fairly good results with the meniscus lens; there is a small amount of barrel distortion to the image, perhaps exaggerated by the film not being held entirely flat.

|

| No.2A Brownie with Fomapan 200 showing light leaks and scratches |

The light leak appeared to be due to the fact that there's a very small gap between the edge of the 120 film, and the sides of the internal frame (nothing to do with the film being panchromatic as is sometimes stated when using cameras with red windows: the film's backing paper itself should be perfectly light tight). This small gap caused some internal reflections, but mostly what appears to be technically irradiation, as the light hits the very edge of the film from behind, and travels sideways into the film base and emulsion. My solution was to make a baffle, a mask insert from thin black card that would sit over the sides of the film and cover this small gap at the edge.

|

| Mask for 120 film |

Given the positioning of the frame numbers on 116 film, rather close to the edge of the backing paper itself, this baffle did partly obscure the frame numbers, but these are just visible. As I've previously written about in my post on the

Zeiss Ikon Cocarette, with 120 film in a 116 camera, the 6x4.5 format numbers appear in the standard 116 red window, and I have been using the same sequence of numbers and marks: advance the film to the first circular mark before the number 3 appears for the first exposure, then 5, the first mark before number 8, the third mark before 10, the first mark before 13, and finally 15. This sequence is not perfect, as there are some slight overlaps between some frames, but it's the closest practical set to achieve six exposures on a roll of 120; being more generous with the film, one could easily get five exposures with no overlaps by just using the numbers 3, 6, 9, 12, 15.

|

| Red window with 120 film and card mask |

I tested this card mask I had made to solve the light leaks when I used the No.2A Brownie for this year's

Take Your Box Camera To Work Day. Although I wasn't testing it in the brightest, sunniest weather, it does appear that this has solved the problems of light leaking when using 120 film; I did also shoot a couple of rolls of film taped to 116 backing paper, where this wasn't an issue, and I was therefore able to use the 116 numbers for the frame spacing. As I've written in relation to other box cameras, I believe it's a fallacy to think that one has to use a slow film with a box camera simply because these would have been the films available at the time. As the manual states, the for instantaneous exposures or snapshots, the widest aperture must be used and the subject should be in broad open sunlight; the middle aperture stop is for snow, sea and clouds settings with no heavy shadows. All other lighting conditions would have been using the time exposure and counted in seconds; for portraits outside the manual recommends using the middle or smallest stop and giving an exposure of one or two seconds. To replicate this experience, one could use a slow, currently available film like

Rollei RPX 25, but this does seem restrictive for using an old box camera for most situations. With modern, faster films, it's therefore possible to use the camera hand-held in different conditions, with smaller apertures, other than for sunny exterior shots as designed.

|

| No.2A Brownie with Kodacolor 116 film (process before July 1961) |

However, when I shot the expired Kodacolor 116 film last year, I did just that. The film was originally 32 ISO when new; more than five decades after its process before date, I rated it at around 6, which meant that I couldn't use it hand held with the No.2A Brownie (I did shoot another roll of a similar age in the

Zeiss Ikon Cocarette hand held, but that was due to its much faster lens). As the cardboard body isn't provided with tripod sockets, for these long exposures, I simply found any flat level surface that was convenient, benches, parapets on bridges, bollards; given that the No.2A has one entirely flat side and base, it's very easy to do this with the camera, covering the lens at the moment of tripping the shutter to eliminate any shake, and then letting it sit for the duration of a couple of seconds to a minute or so. When using 120 film in the camera, the slight cropping of the 116 frame makes for an image of attractive proportions and the meniscus lens proves more than adequate, with the large negative size being very forgiving set against the limitations of the simple box camera itself.

|

| No.2A Brownie with Ilford FP4 Plus |

|

| No.2A Brownie with Ilford HP5 Plus |

Sources/further reading:

No.2A Brownie on Early Photography

No.2A Brownie on the Brownie Camera Page

No.2A Brownie on Brownie-Camera.com

Kodak No.2A and No.3 Brownie manual (pdf) - May 1912

No comments:

Post a Comment