“For it is not a question of presenting works in correlation with their time, but rather, in the time in which they are born, of presenting the time that knows them.”

Walter Benjamin (italics mine)

When Vermeer was ‘rediscovered’ in the nineteenth century, his oeuvre scattered and attributed to others, there was no unified idea of what a Vermeer painting was, and therefore what could be looked at and considered a Vermeer. Now, Vermeer is generally thought of as a painter of quiet interiors, usually with a solitary figure, usually female, with just a few odd paintings lying outside these descriptors. However, in this period of rediscovery, many other artists’ works were attributed to Vermeer, driven by Théophile Thoré’s conception of what Vermeer’s oeuvre should look like. Thorè, writing under the pseudonym Willem Bürger, in his article ‘The Sphinx of Delft’ in the Gazette de Beaux Arts (1866), included twenty-two landscapes and street scenes, around a third of the paintings that he listed as being by Vermeer, seeing the artist as a painter of views (these paintings are now attributed to Vermeer’s contemporaries Jacob Vrel, his near-namesake Dirk Jan van der Meer, and the much later amateur painter Jan van der Laan). That Thorè-Bürger saw Vermeer as a painter of views was no doubt influenced by the impact of his encountering the View of Delft and the Little Street:

"In the museum at the Hague, a superb and most unusual landscape captures the attention of every visitor and powerfully impresses artists and connoisseurs. It is the view of a town, with a quay, old gatehouse, buildings in a great variety of styles of architecture, garden walls, trees and, in the foreground, a canal and a strip of land with several figures. The silver-gray sky and the tone of the water somewhat recalls Philip Koninck. The brilliance of the light, the intensity of the color, the solidity of the paint in certain parts, the effect that is both very real and nevertheless original, also have something of Rembrandt.When I visited the Dutch museums for the first time, around 1842, this strange painting surprised me as much as The anatomy lesson and the other remarkable Rembrandts in the Hague museum. Not knowing to whom to attribute it, I consulted the catalogue: View of the Town of Delft, beside a canal, by Jan van der Meer of Delft. Amazing! Here is someone of whom we know nothing in France, and who deserves to be known!"

[…]

"Later, even before 1848, having returned to Holland several times, I also had the opportunity of visiting the principal private galleries, and in that of M. Six van Hillegom—the happy owner of the celebrated portrait of his ancestor, Burgomaster Jan Six, by Rembrandt—there I found two more extraordinary paintings: a Servant pouring milk and the Façade of a Dutch house,—by Jan van der Meer of Delft! The astounding painter! But, after Rembrandt and Frans Hals, is this van der Meer, then, one of the foremost masters of the entire Dutch School? How was it that one knew nothing of an artist who equals, if he does not surpass, Pieter de Hooch and Metsu?"

In my previous post, Cameras Obscura, I wrote about my own encounters with the work of Vermeer, and of seeing the Little Street while studying A-level art, and of Arthur J. Wheelock Jr.’s monograph on the artist; a section of this book details Delft’s brief artistic flourishing in the mid-seventeenth century - as well as containing photographs of the (then) contemporary Delft (the book was first published in 1981). As a result I had my own imaginary conception of the city long before I travelled there, and one built in a formative stage in my own life. Arriving in Delft by train, after dark, at the very end of last year, walking from the station to the apartment where we stayed, I suddenly found myself in the market square, confronted by the Nieuwe Kerk, familiar from Fabritius’s View, as well as its tower appearing in Vermeer’s View of Delft. Like finding Alice’s grandmother’s house from the film Alice in the Cities in Gelsenkirchen four years ago, written about on my other blog, this confirmation - in a physical reality - of a world as experienced through images, and, as such, this was an imaginative world, an idea, a conception of place invested with something equivalent to a mythical existence, accessed through its representations, although one much more particular than those larger, more widely-held mythologies of Paris or New York for example. My interest in Wim Wenders’ films of the 1970s was based, in part, through my prior experience of reading about the films as a student, without, at the time, being able to see them; reading about, and seeing Vermeer’s (and Fabritius’) paintings as a teenager, and, perhaps, with an intervening period of my life, many years in fact, in which I did not think about them very much, little did I suspect, then, that one day I would find myself in Delft, and, indeed, staying on Nieuwe Langendijk, a street which continues on from Oude Langendijk, which itself runs alongside the Nieuwe Kerk, and is the corner location of Fabritius’ A View of Delft; Vermeer himself was documented as living on on Oude Langendijk in 1660.

|

Delft central station, Kodak Retina IIa with Agfapan APX100

|

Much is made of the contemporary experience of the ‘non-place’, and the new railway station in Delft, the first impression of the city when arriving by train, conforms in some respects to this idea of the non-place, but then, moments later, standing in the market square, there was a feeling, a feeling of being definitely placed, by the Dutch vernacular architecture of course, and by the memory of those second-hand impressions of the city through the work of Fabritius, Vermeer, and de Hooch, and the material commentary of prints, drawings, and maps which often contextualises these artists and others. In writing about Alice’s Grandmother’s House I quoted, then, at length, a passage from Georges Perec’s 'Species of Spaces': “To cover the world, to cross it in every direction, will only ever be to know a few square metres of it, a few acres, tiny incursions into disembodied vestiges, small, incidental excitements, improbable quests congealed in a mawkish haze a few details of which will remain in our memory…” which summed up the particularity of how it felt to be there, then, at that moment; in the same passage, the phrase “out beyond the panoramas too long anticipated and discovered too late” could stand in for the title of this post.

|

Nieuwe Kerk, Delft, Kodak Retina IIa with Ilford HP5 Plus

|

A day earlier, I had been in the Rijksmuseum. As well as the

Maidservant Pouring Milk, I had seen again the

Little Street, this time paired with Velazquez’s similar-sized landscape of the gardens of the Villa Medici as part of the temporary exhibition ‘Rembrandt-Velázquez: Dutch & Spanish Masters’. There’s something about these two small paintings by two artists not known for making views which makes them remarkable; one wonders exactly how they conceptualised what they were doing when they made these works. Of course, there are many paintings like Vermeer’s

Little Street, alike enough that they were at one time attributed to him, and yet unalike, now, that they have become stripped from his oeuvre, given to Vrel and van der Laan, with something about these other paintings, suggesting a fidgety, sentimental or anecdotal quality (apparent, too, or too often, with Pieter de Hooch); however these are all part of a general trend in Dutch art of the seventeenth century that fundamentally re-thought what it was to make pictures, but in the particularity of Vermeer’s

Little Street, and in the

View of Delft, there is something more, a foreshadowing of a tendency which would begin to make itself known over a century later in artists’ sketches from nature. Peter Galassi, in

Before photography: painting and the invention of photography traces the “ultimate origins of photography” to the invention of perspective, an ordered way of seeing the world with everything in its proper place and relation to the viewer; establishing this, Galassi elaborates that it is not the development of perspective construction itself (though necessary) which leads on to the invention of photography, but how, in the hands of artists, it is used:

“The Renaissance system of perspective harnessed vision as a rational basis of picture-making. Initially, however, perspective was conceived only as a tool for the construction of three dimensions out of two. Not until much later was this conception replaced—as the common, intuitive standard—by its opposite: the derivation of a frankly flat picture from a given three-dimensional world. Photography, which is capable of serving only the latter artistic sense, was born of this fundamental transformation in pictorial strategy.”

As an example of this, Galassi contrasts a Renaissance painting known as the Urbino

Ideal Townscape or

Ideal City (c. 1470), in which the space depicted is placed

before the viewer; with Emanuel de Witte’s

Protestant Gothic Church (1669), the viewer is placed

in the space. Galassi describes the two different approaches as depending of two different mentalities: the former, using perspective, in

constructing a world; the latter, again using perspective, but

taking from the world as an already existing arena of potential paintings. (Galassi also describes a new particularity of time in de Witte’s painting: the

Ideal City is suffused with an even light which gives equal clarity to the architecture; de Witte’s painting in contrast shows sunlight breaking up this clarity for a specific time of day - and something analogous is happening with Vermeer’s

View of Delft). Galassi states that, for the historian of perspective, its development and uses do not follow a smooth progression, but, instead, this history is

“…denser in the fifteenth, seventeenth, and nineteenth centuries, when innovative conceptions of perspective were richer than during the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. And its emphasis is not guided by absolute value, for Saenredam will claim attention equal to Vermeer, and the young Corot more than David. Similarly, for a given period, it will favor some branches of art over others. The problem of vision was often most directly posed, for example, in the painting of landscapes and views. This tradition thus receives disproportionate attention; around 1800 it is the entire domain of the most radical experiments in the role of vision in art.”

This “problem of vision” explored in Vermeer’s work may explain his relative obscurity in the century following his death - and his ‘rediscovery’ in the age of the invention of photography. Like Saenredam’s radical compositions (“Not until the late nineteenth century was such a willfully fragmentary and internally discontinuous view the common option of every painter.”), Vermeer’s views are also, in their own way,

anachronistic in conception, rare “forward glances” in Galassi’s phrase, the logic of which would have to wait for the invention of photography to be properly understood: “perhaps one of the ironies of art history that with a Kodak any child might now produce by accident a composition that a great artist like Vermeer had to use all his ingenuity […] to achieve.” (R. H. Wilenski,

An Introduction to Dutch Art, 1928 quoted in Chrales Seymour Jr., ‘Dark Chamber and Light-Filled Room: Vermeer and the Camera Obscura.’)

|

View across the Kolk, Delft, Zodel Baldalux with Ilford FP4

|

Vermeer’s

View of Delft was painted from a viewpoint looking roughly north, across a harbour called the Kolk, outside the city’s walls, towards the prominent Schiedam and Rotterdam Gates, with the tower of the Nieuwe Kerk prominently lit, and the Oude Kerk tower largely obscured. After visiting the Vermeercentrum and the Nieuwe Kerk earlier in the day, finding the location from which Vermeer painted the View of Delft was straightforward: although almost all the buildings depicted by Vermeer have gone, the general topography is the same: the Kolk, the canals branching off into the city from behind where the city gates were, the general street plan, and the Nieuwe Kerk tower of course (visually, the twin spires of the 19th-century Maria van Jessekerk echo the absent spires of the Rotterdam Gate on the skyline to the right of the Nieuwe Kerk). Wanting to make

something about the experience of being in this place, but not knowing how to react, I filmed the reflections of the skyline in the water - the reflections being one of the most remarkable aspects to the painting - with the outline of the Nieuwe Kerk tower clearly seen against the late afternoon sky, its silhouette dominating, in a manner essentially absent in the painting (as it is brightly lit, with the sky behind it, the reflections below only pick up the dark masses of the tree or trees and the Rotterdam Gate in shadow either side of the more distant tower). Perhaps this was appropriate - filming a reflection of the tower which is impossible to discern in the painting - as the current tower of the Nieuwe Kerk is

not the same as that depicted in the

View of Delft. The Nieuwe Kerk was struck by lightning in 1872 (having been struck and partially destroyed before in 1536; the rebuilt tower that appears in Vermeer’s painting survived the ‘Delt thunderclap’ of 1654) and the tower rebuilt a second time as a result; the rebuilding of the upper stage of the tower used Bentheim sandstone, blackened through a reaction to atmospheric pollution, in contrast to the colour of the stage below, which gives the erroneous impression of having been scarred by fire. As well as not being the same tower reflected in the film, it is of course not the same water making its reflection.

|

Bolex B8, Retina IIa with Adox Scala 160

|

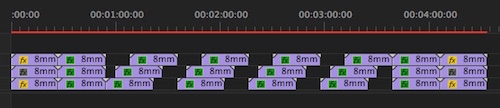

Although I didn't know it at the time, the Double-X film I shot here with the Bolex B8 wasn’t exposed properly due, as I later surmised, to the variable shutter being stuck in a near-closed position: I didn’t see the results until developing this roll of film some time later; however, as this footage was on the first roll of 8mm film from the trip that I developed, it did mean that I (rather belatedly) made a number of tests before developing the other two rolls of film shot in Delft, which, particularly in the case of the 'Pouring Milk' film, meant I was able to adjust the developing times sufficiently to get as good a result as was possible from the latent images. I have excerpted a short sequence as an animated GIF below; the thinness of the negative shows any dust incredibly well, a result of a lack of cleaning before scanning and ad hoc processing conditions - essentially attempting to improvise a means of drying 25ft of 2x8mm film in a hurry.

One reason for shooting film, rather than digital, were the sense of having a physical artefact, an indexical link to the contingencies of the location itself, ideas which probably do not hold too much weight in the digital present, especially with the results digitised and disseminated through a digital medium; regardless, what is recorded onto the physical medium is something other than a provisional interpolation of data (and, if ever exhibited, a positive could be printed from the negative and projected). In Ways of Hearing, Damon Krukowski attempts to encapsulate how it felt as a musician to be recording to tape in the 1980s, not an entirely unsympathetic analogy:

“In that analog studio, there was a feeling when the tape started rolling that this was the moment we would capture-a feeling of time moving both more slowly, and more quickly than usual. Like when you’re in an accident. Each split second is suddenly so palpable, as if you’re living in slow motion. Yet what do we say when it’s over? It all happened in an instant.Analog recording is like an accident in other ways. On tape, there was no “undo”. You could try again, if you had the time and money. But you couldn’t move backwards. What’s done is done, for better and worse.”

Two days after visiting its location, we took the tram from Delft to the Hague to visit the Mauritshuis and see Vermeer’s

View of Delft. Any attempt to describe the experience of finally seeing a painting familiar from reproductions for many years would be entirely inadequate. In real life, the

View of Delft is both familiar and surprising (or at least to me, in some aspects, especially the thickness of the paint in some areas, notably in the near foreground) and one can appreciate the impression it made on Thorè-Bürger around the time photography was being invented. As a result, while still in Delft, I decided to revisit the viewpoint again. Having initially been to the spot with a camera but no clear idea, I needed to give myself a logical structure this time; in the interim, I had shot

Pouring Milk and had used a duration for that film from a measure of how long visitors in an art gallery look at a work of art: while trying to find a definitive average, a different answer which I had also turned up was 17 seconds. Determining that, if I used a whole side of my last roll of 2x8mm film that I’d taken with me to Delft, shooting at 12 frames per second rather than 16fps, its duration should be long enough to contain 17 separate shots of 17 seconds each. Any response to Vermeer’s painting would only ever be inadequate; any attempt to communicate the personal experience of how it felt to be standing there, in that same location, looking over Delft from that same viewpoint, with the painting fresh in my memory, would also be inadequate. Acknowledging the futility of trying to engage meaningfully with such a canonical work of art, my approach was to

not film the view itself: the film is built up from details around the viewpoint as it currently exists in the historical moment that I was there, then.

|

| Thomas Elshuis, Panorama, Zodel Baldalux with Ilford FP4 |

Facing the view, a raised platform above the quayside of the Kolk provides an approximate elevation to the correct viewpoint: Vermeer may have used the second floor of an inn which stood on that spot in the seventeenth century to make his painting. This platform is made from brick and paved, but when I was there some work to it was in progress or had just been finished: there were pallets of building materials collected there, paving bricks and kerbstones just at the right point of the platform overlooking the view. Behind the platform there was a patch of muddy, sandy ground which had evidently been re-landscaped recently, with a circular area of cobbles having been removed. In the middle of winter this was bare of grass, imprinted with footprints and tyre-tracks. Curving around the back of the raised platform, a steel structure supports a set of printed, translucent panels. This is a work of art called Panorama by Thomas Elshuis (although in the Dutch text, it seems to be called Gezicht op Delft - View of Delft), which brings together Newton’s discovery of the refraction of white light into the visible spectrum of colours with van Leeuwenhoek’s microscope, represented by drops of water, magnifying the sand from the bed of the Schie, the canalised river which meets the Kolk from Rotterdam and Delfshaven, and, perhaps, is also a reference to the sand incorporated into the paint in some passages of Vermeer’s painting. Photographs of this ‘folly’ (as Elshuis calls it) on the art in Delft website show sunlight streaming through it, highlighting the stained glass-like qualities of the translucent panels, making sense of the references to Newton and van Leeuweenhoek, an effect quite absent on a grey January morning. After I shot the film, behind the raised platform, partially covered with dirt, I discovered the two metal plaques set in the ground behind the structure which detail this piece of site specific artwork in Dutch and English.

|

Metal plaques, Kodak Retina IIa with Agfapan APX100

|

Having shot the two rolls of (new) Double-X I’d taken with me, I had one roll of 2x8mm film left. This was Orwo UP21 with a process before date of November 1982. I had bought two rolls of this online with the same date, in the same lot, and had previously tested a short length cut from the other roll before travelling, and found the best exposure index for the film stock was around 12; I was also developing this as a negative: although nominally a reversal or transparency film, unlike some black and white reversal ciné film I’ve used, the Orwo film does not have a colloidal silver anti-halation layer, which means it can be developed as either a negative or a positive.

|

2x8mm Orwo UP21 film

|

I shot at 12fps for the increased duration this would provide, and this would incidentally mean a slower shutter speed, but the grey overcast morning light when I returned to the site was so low, I felt as though I needed an extra stop in filming, and rated the film at 24 rather than 12 (the light levels also meant that most shots were taken with the lens wide open, or close to wide open, and the accuracy of focus has suffered as a result). At the time I thought I might be able to extend the developing time a small amount to compensate. There was a general logic to the sequence of shots, although essentially improvised, moving from the very small, close-framed shots of the platform facing the view, to the final shots which show the artwork by Elshuis, but in fragmentary details. The editing of the film was done in camera, and the length of the film is shown in its entirety, with both leader and trailer. I loaded the film and unloaded to turn it over in a changing bag, meaning that the film wasn’t exposed to light in either operation, in order to use the whole length of the film. When developed, it was clear that the film had been exposed while wound on its spool, but I kept this bleached-out section, containing the identification code, the circular holes punched through the film at the start: light through these holes has imprinted itself through a couple of layers of the film; a wavy line, the shadow of the rubber band securing the roll can also be seen to the right hand side of the image.

When I came to develop the first roll of 2x8mm Double-X shot on this trip, as soon as I took the film out of the tank, I realised that something was wrong: it looked underdeveloped, or so I thought. I subsequently shot a number of short tests of both film stocks I had used in Delft, Double-X (and in doing so, discovered that single-perforated 16mm - having used all my 2x8mm perforated Double-X - would run through the Bolex B8, at least well enough to test the exposure), and the Orwo UP21 from the part-used roll I’d already tested in a still camera and not taken to Delft. I shot three test lengths of the UP21, decreasing the developer dilution and increasing development time as I went, in my attempts to get a usable result. Making these tests I realised - only gradually - that the camera was underexposing by around three stops, and my only explanation for this was that the variable shutter was stuck near closed, so in the shooting of this film, I had effectively exposed it around

four stops faster than the exposure index I had tested for. As well as increasing time and decreasing the developer dilution, I also took two rather more extreme technical approaches: first, I flashed the entire roll of film in an attempt to raise the shadow values (as I would be pushing the film, the contrast would be increased, and I was expecting no or little shadow detail at this stage, although I had been filming in very flat, diffused light). To do this, I ran the whole roll of film through the Bolex again, double-exposing it by filming a featureless white wall - with the lens out of focus - and three stops below a meter reading taken from that wall. As before, I loaded, unloaded to flip the film spools, and finally unloaded the film using a changing bag after exposing both sides. I developed the film with Ilfotec LC29, diluted 1+9, for 20 minutes at 20ºC. The second approach was to tone the whole film with selenium toner after development, with the idea that this would act as an intensifier on the negative, providing a little more density. The end results are still far from what I had hoped. It’s possible that the toner may have simply increased the overall graininess of the negative, the fog of age; incidentally, the edge markings on the film look considerably blown out from the push processing. Due to the poor light levels, camera faults, and processing issues, the resulting images on the film are underexposed, hard to read, obscure. Titling it 'A View of Delft' is an assertion of what it shows, factually accurate, despite there being little of the location that is clearly recognisable in the film (although possibly I should call it 'Seventeen Views of Delft'). I have recently become interested in how the title of an artwork functions, how the title, as extrinsic content, is both integral to an artwork yet stands apart, separate from the object itself, a content which brings the viewer into a unique relationship to the art object, a relationship which, in some senses, ‘creates’ the art

work. In an essay called 'Entitling', John Fisher asserts that:

“Titles are names which have a sense; they call for responses. They determine, to a degree to which significant attention has never been given, interpretations and other acts.[…]

Not all artworks are titled. Not all artworks need to be titled. But when an artwork is titled, for better or for worse, a process of interpretation has inexorably begun.”

Vermeer’s painting, the

View of Delft has a declarative title which aids little in the process of interpretation, its need is small, especially if one is familiar with the city it represents; indeed, as with the title of

Maidservant Pouring Milk, now more commonly known as the

Milkmaid, as described in the previous post, the painting hasn’t always been simply the

View of Delft: Thorè-Bürger knew it as

View of the Town of Delft, which seems unnecessarily wordy, but a descriptive title suffices nonetheless. The changing function of works of art, through changing conditions of production and consumption, demand that, in many cases, the title has more work to do than might previously have been the case. As a title,

A View of Delft alerts the viewer

to the gaps in what it represents, perhaps appropriate to the contingent nature of working with a physical medium, film, the conditions of its making, and its unmet ambition in an attempt to meaningfully encounter Vermeer’s

View of Delft.

Bibliography

Walter Benjamin, ‘The History of Literature and the Science of Literature’ from Poesie et revolution, Paris 1971, p14, quoted in Hubert Damisch, The Origin of Perspective, translated by John Goodman, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1994; originally published as L’Origine de la perspective, Flammarion, Paris 1987

Daniel A. Fink, ‘Vermeer’s Use of the Camera Obscura - A Comparative Study’, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 53, No. 4 (Dec., 1971) pp. 493-505

John Fisher, ‘Entitling’, Critical Inquiry, Vol. 11, No. 2 (Dec., 1984), pp. 286-298

Peter Galassi, Before Photography: painting and the invention of photography, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1981 www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2267

Jonathon Janson, 'Essential Vermeer' website: http://www.essentialvermeer.com/

Damon Krukowski, Ways of Hearing, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2019

Georges Perec, ‘Species of Spaces’ in Species of Spaces and Other Pieces, translated by John Sturrock, Penguin 2008

Charles Seymour, Jr., 'Dark Chamber and Light-Filled Room: Vermeer and the Camera Obscura', The Art Bulletin, Vol. 46, No. 3 (September 1964), pp.323-331

Sandra Spijkerman, ‘Kunst in de Openbare Ruimte/Gezicht op Delft’, https://delft.kunstwacht.nl/kunstwerken/bekijk/330-gezicht-op-delft See also https://thomaselshuis.nl/

Arthur K. Wheelock Jr, Vermeer, Thames and Hudson, London 1988

Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., C. J. Kaldenbach, Vermeer’s View of Delft and his Vision of Reality, Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 3, No. 6 (1982), pp. 9-35