|

| Kiev-30M (open, the red dot, just visible, indicates the shutter is cocked) |

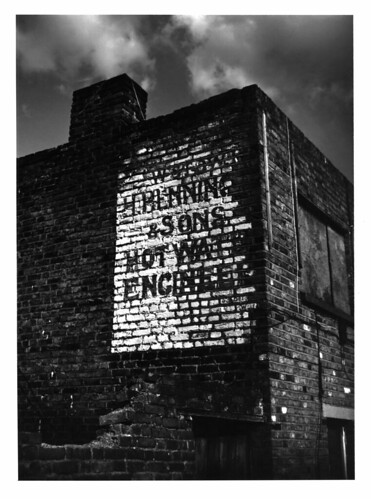

The

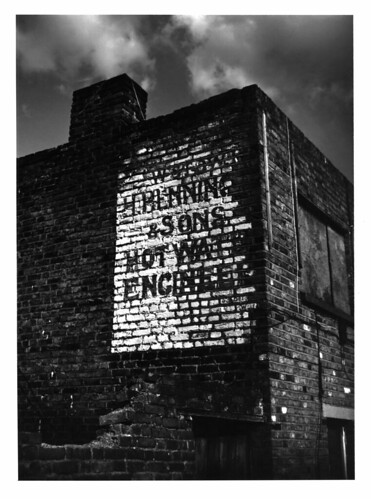

Kiev-30M is the penultimate model in a series of 16mm

subminiature cameras produced by the

Arsenal factory in Kiev, Ukraine. The original model of the Kiev subminiature series, the Vega, was based very closely on the

Minolta-16. Like other Eastern Bloc post-war cameras copied from (mostly German) cameras, the Kiev Vega then evolved separately from the camera it was based on as the design was modified with each successive model. The second version of the Kiev Vega added the ability to focus the lens, something that the Minolta-16 cameras didn't have until much later models (though there were close-up filters available). The cassette was redesigned for the Vega 2 with a

smaller spool than that of the Minolta-16, increasing the number of

frames on a roll of film from 20 to 30. The Kiev Vega 2 was succeeded by the Kiev-30, which utilised a larger frame size (13x17mm) in a redesigned body. This larger frame size reduced the number of frames on a roll of film from 30 to 25 (although I wonder that the reason for the camera being called the Kiev-

30 is due to this change to the preceding model). The Kiev-30M had a couple of minor changes from the Kiev-30, simplifying the camera by losing the PC flash sync socket and the manual exposure calculator on the back. The last 16mm model from Arsenal was the Kiev-303, which featured a redesigned plastic body in a variety of colours, and had four speeds rather than three, with 1/125th and 1/250th instead of the previous top speed of 1/200th.

|

| Kiev-30M box contents |

My Kiev-30M came in a box set from the

Lubitel shop in St Petersburg (I wrote a post about the camera shortly afterwards, but, recently, having used it more, I felt it was worth substantially rewriting this). Although the box had seals that had been broken, everything inside appeared as new. As well as the camera, the contents are: a camera strap and case; a second film cartridge, in a plastic box; a reducing frame for using the 16mm negatives in a 35mm enlarger; a reel to fit in a developing tank; the camera manual; and a piece of paper with a list, possibly of suppliers. The manual is dated with a stamp of April 1989. The three rolls of

Svema Foto 65 film (which came from a different camera box) have a 'develop before' date of 'IX/1986'.

|

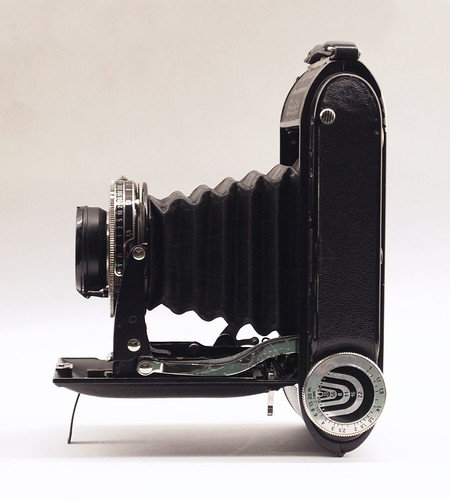

| Kiev-30M (closed) |

The Kiev-30M is very compact 86x47x28mm when closed, extending to 108mm wide when open. Despite the camera's small size it is relatively heavy at 190 grams as the camera is constructed almost exclusively from metal and is entirely manual and mechanical. The controls visible on the side of the camera are two wheels, one to set the limited range of shutter speeds, 1/30th, 1/60th and 1/200th; the other controls the aperture, from f3.5 to f11. On the underside of the camera is a window showing the exposure number. To take photographs, the camera's outer body shell slides to the open position (as in the image at the top of this post), which uncovers the shutter release and focus control; the two glass windows align to the viewfinder and lens. The window that covers the lens can be removed by sliding it out sideways: the Minolta-16 had filters which could be inserted here, although the Kiev-30M box didn't come with any filters. The lens is a 23mm Industar-M, which on the 13x17mm frame size provides roughly a (horizontal) 40º angle of view. The lens focuses down to 0.5 metres, markings are also provided for 1 and 2 metres, in black, while picked out in red are the infinity mark and, close to this, a dot. The red dot is the focus setting for 5 metres, which serves as a hyperfocal position for all apertures. Also uncovered on the camera's top plate is a film plane indicator, while the serial number is engraved on the underneath.

|

Depth of focus table from the manual;

the '15' in the focus setting column must be a misprint for 0.5 |

Opening the camera cocks the shutter and advances the film: the shutter appears to be a guillotine-type, and when cocked, there is a red dot to indicate this visible in the lens window. The push-pull film advance does mean that opening and closing the camera without taking a shot results in a blank frame, but without opening the camera it isn't possible to look through the viewfinder.

|

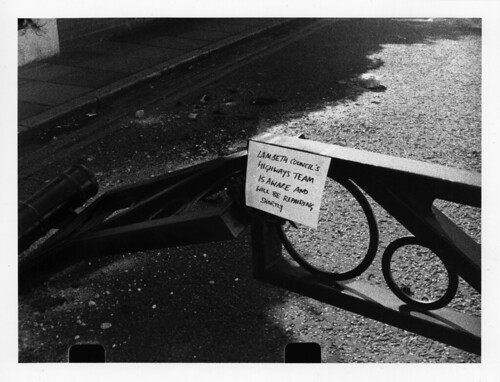

| Kiev-30M opened for loading |

To load and unload the Kiev-30M, the outer shell has to be removed completely: there is a catch which can be released only when the camera is in the open position. This lays bare the exposure counter wheel: when loading a film, this needs to be manually reset by aligning a red line on the wheel with another line on

the bottom plate. The film cassette is loaded by opening a cover on the top. The film cassettes have two chambers, one smaller, without a spool, for the supply side, with take-up side being slightly larger to accommodate the spool. As a legacy of the camera's origins as a copy,

Minolta 16 cassettes are said to be compatible with the Kiev cameras. With a frame size of 13x17mm rather than 10x14mm, the Kiev-30M is designed for unperforated 16mm film (perforations will be visible in the image area). The cassette takes a 45cm length of film: the frame counter goes up 25, with every third number represented with two dots between (there is also a red dot between the numbers 16 and 19). When loading the cassette, a small pressure plate with a tiny tab needs to be pulled back to slide the section of film between the two chambers into position, not immediately obvious on a first attempt.

|

| Kiev-30M cassettes |

|

| Kiev-30M with expired Svema Foto 65 film |

I shot two of the Svema films while in St Petersburg, loading the cartridges inside the hotel room cupboard with all the lights in the room turned off. I finished the second roll of film once I had returned home and stand developed it in Rodinal diluted 1:100 for one hour, using the technique I'd tried with film from the

Mamiya-16 Automatic of taping the 16mm film, emulsion side out, to a length of 35mm film and loading this on a normal 35mm developing reel. The film is

Foto 65, the 65 being the film's

GOST value,

the Russian speed scale, equivalent to 20 DIN/80 ASA. Translating the

text on the box, the film was originally priced at 10 kopecks, surely

very cheap even 30 years ago, and has a developing time of 5 minutes, although there's no indication of the developer required. The price of the film refills perhaps reveal why the 16mm subminiature format persisted in the Soviet bloc (the last Arsenal subminiature camera, the Kiev-303, was produced c.1990), while elsewhere Kodak's 110 format essentially used market dominance to push out all the previous competing 16mm systems twenty years earlier, where most cameras had proprietary cassette designs.

|

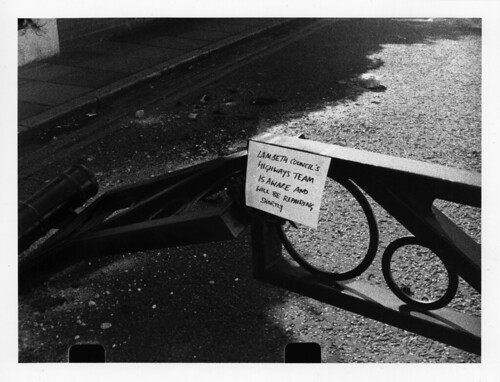

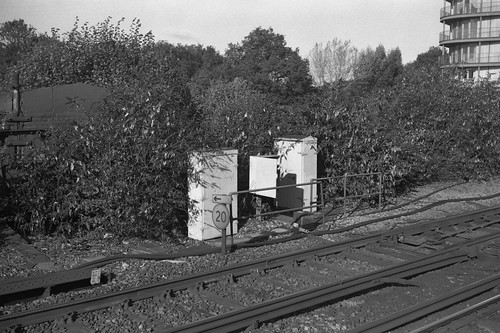

| Kiev-30M with Kodak WL Surveillance 2210 film, scan from negative |

When loading the cartridges with 16mm film from 100ft rolls, it is possible to get more than 45cm of film into the supply side chamber, and it's relatively easy to get around 30 rather than 25 frames, although the frame counter doesn't turn around any further after the number 25. With single perforated film, if the film is loaded into the cassettes with the perforation side towards the plastic bridge between the chambers, the perforations appear at the bottom of the frame, to my mind less obtrusive to the resulting photographs. As I found when using the

Mamiya-16 Automatic, subminiature negatives are too small when scanned with flat bed scanners to properly resolve detail. To really appreciate the results from the camera, I recently printed a number of shots from the Kiev-30M in the darkroom. The 16mm reducing frame which came in the box proved very useful when printing, and given the small size of the negatives, I had to wind the enlarger head almost to the top of its post to achieve a print size of 5x7 inches. The images below are all scanned from prints on Kentmere VC Select paper.

|

| Kiev-30M with Kodak WL Surveillance 2210 |

|

| Left: scan from negative at 3200dpi; right scan from 5x7 inch print for comparison |

|

| Kiev-30M with Kodak WL Surveillance 2210 |

|

| Kiev-30M with Kodak WL Surveillance 2210 |

The

Kodak WL Surveillance 2210 film for the shots above is a 400 ISO film, and the grain is particularly pronounced as a result of the subminiature frame using approximately a quarter of the film area compared to a standard 35mm frame. I also shot some Agfa Copex HDP 13 microfilm with the Kiev-30M (although not stated, it's a reasonable assumption that HDP stands for

High Definition Panchromatic). Typically for a microfilm, it's very slow and very high contrast, but extremely fine grained, which is a great benefit to the subminiature frame size. My first tests with stand development in R09 One Shot at 1+150 suggested an exposure index of 25, but I subsequently shot another roll rated 16 and using a developer dilution of 1+200, which provided better results. The images below were printed on Kentmere VC Select with a 00 Mulitgrade filter, the lowest contrast possible when printing (it is easier to reduce contrast further when scanning).

|

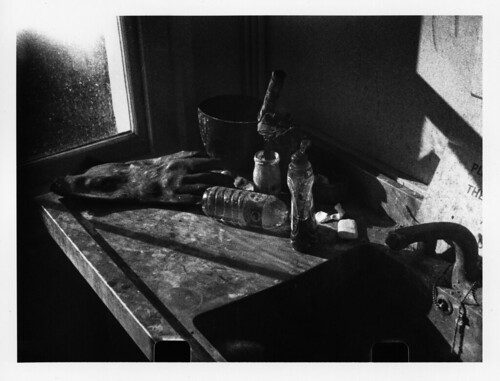

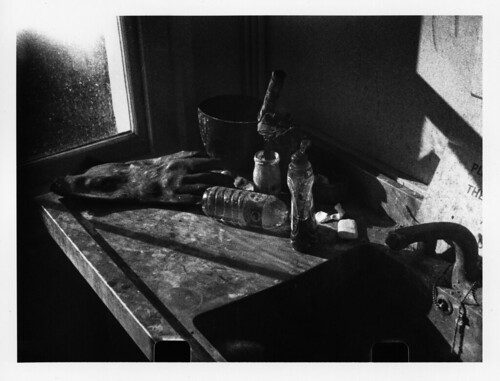

| Kiev-30M with Agfa Copex HDP 13 |

|

| Kiev-30M with Agfa Copex HDP 13 |

|

| Detail from the above image showing fine grain structure and high resolution |

The enlarged detail above demonstrates both the high resolution of the Agfa Copex HDP film and the resolving power of the lens in relation to the negative size. The sticker in top left is approximately 0.6mm high on the negative: the small lettering in the roundel on the sticker itself which is just legible is considerably less than a tenth of the size of the sticker. Evidently the film resolution exceeds that of the lens, but the extremely fine grain makes it ideal for the subminiature format, although the inherently high contrast means that it has very little latitude and may be more suitable for low contrast scenes and subjects, although both images above were taken on a bright sunny day, and the slow speed of the film is more appropriate for bright conditions.

As with many cameras from the former Soviet Union, the Kiev-30M is not without problems. The push-pull frame advance is not always reliable: occasionally the shutter does not cock, and so a frame is wasted in opening and closing the camera again; the catch on the underside of the body can be forced under the outer casing itself, the remedy to this is to bend this catch upwards to engage the outer casing more securely (Minolta cameras abandoned the push-pull advance as new models were introduced after the Minolta-16 II). I have also had odd vignetting on a number of frames, such as in the last shot above, which may be due to the shutter not opening fully. The cassettes are prone to light leaks, this happens more with perforated film. The limited aperture and shutter settings can fall a little short when using a fast film in bright light: 1/200th at f11 with a 400 ISO film in bright sunlight means accepting some overexposure (a yellow or neutral density filter would help in such circumstances). Conversely, a faster lens and a B setting would be useful for low-light situations. Set against these issues, the Kiev-30M is enjoyable to use for a number of reasons: its small size, when closed, easily the smallest camera I own; 16mm film is very cheap by the frame, a standard 100ft/30.5m) roll will fill many cassettes at 45cm each; and the simplicity of the camera itself.

Sources/further reading:

Kiev 16mm cameras on SovietCams.com

Kiev 16mm variations on Submin.com

Soviet-era subminiature camera list on Commie Cameras

Kiev-30M variations on Fotoua.com

Kiev-30M on USSRPhoto.com