As with photography, on which it depends, the invention of cinema has many claimants and each have their advocates; and, like photography, cinema was equally an idea whose time had simply arrived, largely as a result of other inventions, other technologies, the most important being photographic emulsion applied to a flexible base - film. If the cinema is understood to be a communal, theatrical experience, with an audience watching a projected image from moving photographic film, the first demonstration of projected film to a paying public belongs to the Lathams - Major Woodville, and his two sons Otway and Grey. With the exception of the eponymous loop, the Lathams are forgotten cinema pioneers, despite their first public projection in New York, May 1895. Like the Skladanowsky brothers, showing their first films in Berlin that November, the Lathams are treated as something of a footnote in cinema history due to the inferiority of their technology - the Lumière brothers are more popularly given credit for ‘inventing’ the cinema when they projected films before a paying audience in Paris, in December 1895.

On last year’s Expired Film Day, I shot a short film on expired film; intending to do the same this year, the inspiration came from two distinct aspects of Lathams’ story. The Latham brothers were suitably impressed after seeing Edison’s kinetoscope that they went into business as the Kinetoscope Exhibition Company with their father, and an engineer, Enoch J. Rector. After successes filming their own loops and engaging Edison’s William Kennedy Dickson to increase the lengths of the film inside the kinetoscope - specifically to film rounds of boxing matches - the Lathams, with Dickson and Eugene Lauste, a former Edison employee, embarked on a new company, Lambda, with the aim of producing a projector for their films. The Latham's first tests were made in early 1895: “The necessary motion-picture camera was constructed and then tried out on the night of 26-27 February, with Otway Latham and Dickson filming a swinging light.” The use of this swinging light for their first tests is evocative - although not explicitly stated as a light bulb - but I would like to believe that, if it was, its use seems to be an unwitting reference to Thomas Alva Edison. Edison claimed to have invented the lightbulb, despite prior claims by Joseph Swan and others; the Lathams drew on Dickson's expertise while he was still working with Edison, before he left to pursue the motion picture business with the Mutoscope and Biograph Company: one imagines that Dickson, who worked for a number of years on Edison's kinetoscope, perhaps without feeling like he gained the credit he deserved, worked with the Lathams on projection against Edison's resistance to it, before leaving the Edison Company for greater autonomy. Edison was left to catch up with the projection business, buying out the Phantoscope, renaming it the Vitascope, which made its first showing in April 1896.

|

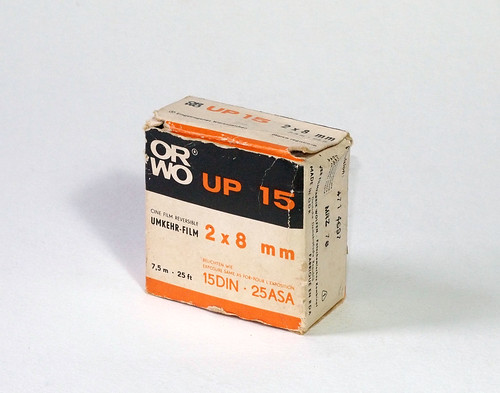

| Orwo UP 15, develop before March 1976 |

|

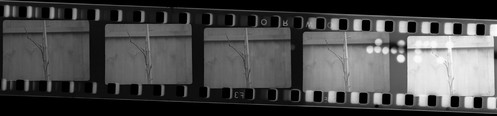

| Orwo UP15 test roll |

For the first of two passes of the double-8 film through the camera, I simply filmed a swinging light bulb; the second pass, I filmed another double-8 camera, open, showing a test roll moving through its internal mechanism: that the Lathams are remembered in cinema is through the invention of the Latham loop (although probably an innovation by Eugene Lauste rather than the Lathams themselves). The best description of the Latham loop comes from Ethan Gates’ The Latham Eidoloscope: A Cautionary Tale in Primacy:

[The loop is] a purposefully slack piece of filmstrip, thrown out both before and after the exposure window in the threading path. When the intermittent apparatus temporarily stops the film, the continuously running rollers take up the slack from the loop following the exposure window, while simultaneously restoring the loop immediately preceding the window; after the moment of illumination and registration on the emulsion, the intermittent is then able to advance the strip forward by a frame by taking up the slack from the preceding loop, while restoring the loop following the window.The arrangement of the two reels inside the camera, and the direction that the film is fed through the intermittent mechanism creates two small loops, which provide the necessary slack. Wanting to use both sides of the film at the same time, and the right way up, meant that on the right hand side I filmed the camera upside down. As a result it is shown running backwards, but this seemed preferable to having the swinging light moving in reverse, whereby it would speed up its motion, rather than slow down. As the camera that I filmed running does not have a very strong motor, it wound down quite quickly, but, in reverse, it is static and then starts up as the film runs. Having to feed the film through the camera when loading also meant that each side’s images had a period of blank film before shooting, but could then be shot to the very end of the roll, so each duration is stepped, out of sync; this also has the effect of showing the light on its own, nearly still, at the end.

Perhaps, ultimately, notions of priority in broadly collaborative fields such as the cinema matter less than the collective endeavour. The Lathams and the Skladanowsky brothers both produced technologically inferior systems, but which were seen by a paying public in 1895, prior to the Lumières’ famous screening at the Grand Café in December; however, the Lumière brothers had also demonstrated their projector to a private audience in March 1895, a month before the Lathams’ press screening - and their cinématographe, a camera, printer and projector in one device, lent its name to the institution on which it depended. However, the newspaper report of the Lathams’ first public screening prophetically understood, even then, the capacious nature of film:

“Life size presentations they are and will be, and you won’t have to squint into a little hole to see them. You’ll sit comfortably and see fighters hammering each other, circuses, suicides, hangings, electrocutions, shipwrecks, scenes on the exchanges, street scenes, horse-races, football games, almost anything, in fact, in which there is action, just as if you were on the spot during the actual events…”

New York World, 28 May 1895

Sources/further reading:

Ethan Gates, The Latham Eidoloscope: A Cautionary Tale in Primacy

The Lathams Build a Projector - Film, Pictures, Eidoloscope, and Machine

Woodville Latham on Victorian-Cinema.net

https://www.britannica.com/art/history-of-the-motion-picture - which only mentions the Lathams in relation to the Latham loop.

No comments:

Post a Comment