|

| Front: Efke R100 127 film/Back: Fomapan 200 120 film for comparison, boxes and film rolls |

127 film is a paper-backed roll format, originally introduced by Kodak in 1912. In many respects similar to 120, the negative size depends on the camera:- the original 'vest-pocket' cameras took 4x6cm exposures; in the 1930s a 'half-frame' format of 4x3cm was introduced, and also a 4x4cm format for the original 'Baby' Rolleiflex, a scaled down version of the Rolleiflex. The paper backing has two sets of numbers: 1-8 for 4x6, and 1-12 for 4x4; cameras for the 4x3 format have two red windows to use the 1-8 set for sixteen exposures: the film is advanced so each number appears twice, once in each window. At the time of writing, two companies currently manufacture 127 film,

Efke and

Maco under the Rollei brand, and there are also colour films from

Bluefire, and Maco, which are spliced from larger rolls of film.

|

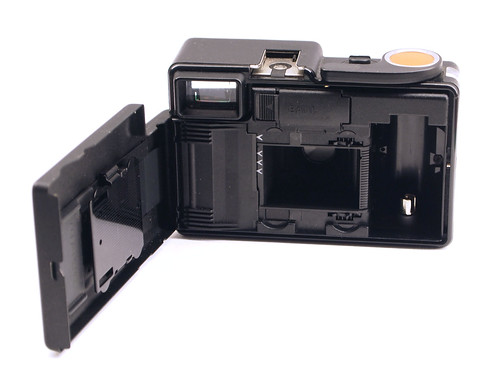

| Kodak Brownie Starmite camera, taking 127 format film |

My interest in the format was piqued by the fact I had a Kodak Brownie Starmite which uses 127 film, and I had never used it. The Starmite is essentially a simple box camera with a flash unit attached. It has a fixed-focus plastic lens, a single shutter speed, and two aperture settings, marked 'Color' and 'B&W'. This was given to me years ago in its

original box. There were two films in the box,

Kodak Verichrome, and Efke R21, both out of date. The Efke film is obviously newer, and I doubt original to the box set, whereas perhaps the Kodak Verichrome is original. As I don't collect cameras just for the sake of collecting, I wanted to use the camera before disposing of it and I didn't want to use the old films in the box just to test it, so I bought some Efke R100.

Efke R100 test roll shot in Kodak Brownie Starmite

The resultant photographs are typical of a cheap box camera: the lens is fairly sharp in the middle, but with the focus falling off at the corners. Interestingly, the Starmite has a

curving film plane, which I imagine is designed to reduce this effect. A couple of the other images on the film show that the film wasn't always kept tight to the film plane, as evidenced by the

wobbly edges to the film rebate. I haven't been able to find out anything about the 'Dakon' lens that the Starmite is fitted with, but I imagine it is of the meniscus type.

One can speculate as to why the 127 format has survived this long, with no new cameras made for 127 film since c.1970, whereas other film formats which were used in greater volumes more recently have quickly become obsolete, most notably the two 'easy-load' formats aimed at consumers,

126 and

110. The overriding reason appears to be the higher quality of cameras made for 127 film, as opposed to 126 and 110 (with the exception of the

Pentax 110 SLR): cameras for these formats were generally (like the Brownie Starmite) simple point-and-shoot snapshot cameras. In the 1950s there was a resurgence in the format with the second version of the Rollei 'Baby' Rolleiflex, and a whole series of Japanese TLR cameras following the

Yashica 44, which were essentially scaled down version of medium format cameras, using lenses, shutters and other components of comparable quality, hence the use of 'Baby' to refer to these cameras.

|

| Zeiss Ikon Ikonta 520/18 - Baby Ikonta camera |

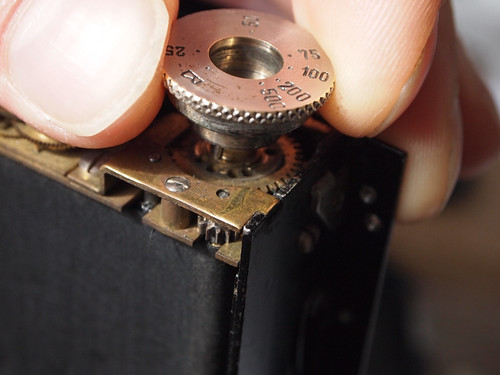

I subsequently bought a

Zeiss Ikon Ikonta 520/18 folding camera- otherwise known as the 'Baby Ikonta', a 127 version of the original Ikonta. Dating from the 1930s, this camera has a Compur-Rapid shutter and a Novar f3.5 lens (the top of the range has a Tessar lens). When folded the camera is comparable in size to a modern digital compact, easily pocketable, yet produces a negative nearly twice the size of a standard 35mm frame. Having shot a couple of rolls of film with the camera, I noticed that despite the film backing having 8 numbers Efke R100 has 18 numbers in the film rebate, and quite a lot of film either end of the sequence of negatives. It was very easy to shoot a 17th frame on the Baby Ikonta, simply by an extra 3/4 turn on the winding knob after the final number on the film backing (I used the words 'Made in Germany' on the knob to check the position: looking at the letter at the 12 o'clock position, I turned this to 9 o'clock to shoot the final frame). It would be less easy to shoot an 18th frame, simply as this would mean taking a shot before lining up the first number on the film backing with the first red window.

|

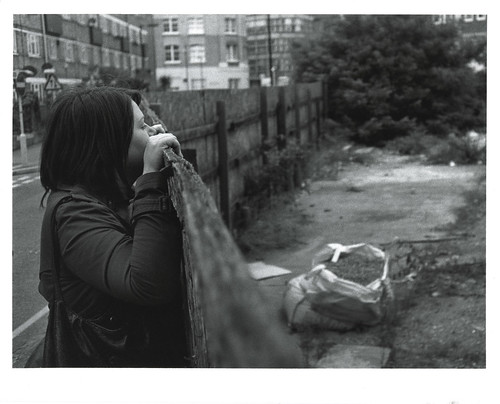

Test roll from Baby Ikonta 127 folding camera, Efke R100,

developed in Rodinal 1:50, 12m30s at 18 degrees C. |

Sources/references/further information:

http://camera-wiki.org/wiki/127

http://www.onetwoseven.org.uk/

http://www.flickr.com/groups/127/

http://www.nwmangum.com/Kodak/FilmHist.html