Beginning this blog six years ago, I did have an idea that it could also include posts concerned with the moving image on film. Growing up in the 1980s, I was aware of Super 8, but this was something that other families had; at the same time, cine film was being supplanted by home video. It wasn't until the 1990s when I was given an Elmo Super 8 camera as a student that I shot a couple of rolls, but the expense of doing so no doubt prevented me from shooting more.

Super 8 succeeded the 'standard', 'regular' or 'double' 8mm format. Kodak had originally introduced the 8mm format in 1932 by taking double-perforated 16mm film, doubling the perforations, and designing a camera which would expose a series of frames (one per perforation) on one side of the film; at the end of the roll, the film was flipped over, exposed in the camera again on the other side of the film, and then split into two 8mm wide lengths, now perforated on one side only, and then the two ends would be spliced together to make a continuous 8mm roll. The Super 8 format appears to have been inspired by Kodak's success with the

Instamatic film cartridge: a fool-proof, easy to load (and unload) system. Kodak took 8mm film, reduced the size of the perforations to be able to increase the image area (which is where the 'super' prefix comes from) and encapsulated the film in a plastic cartridge. At the same time, Fuji applied similar principles to come up with the

Single 8 cassette. Both formats, but especially Super 8 with Kodak's market dominance, made regular or double 8mm obsolete. Although some earlier cartridge systems had been tried, double 8 film cameras generally used a small roll (7.5m) of film on a metal or plastic spool; when loading the camera, as with many still cameras, the ends of the roll are exposed and are sacrificed as leaders, whereas in the Super 8/Single 8 cartridges only a very few frames are so exposed.

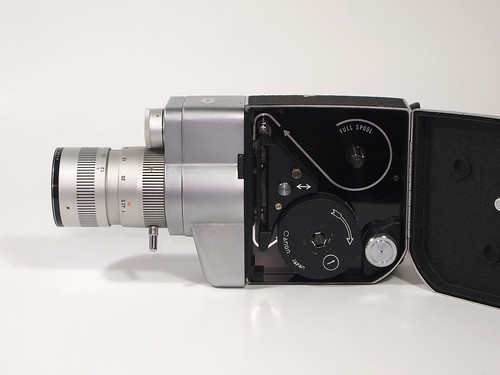

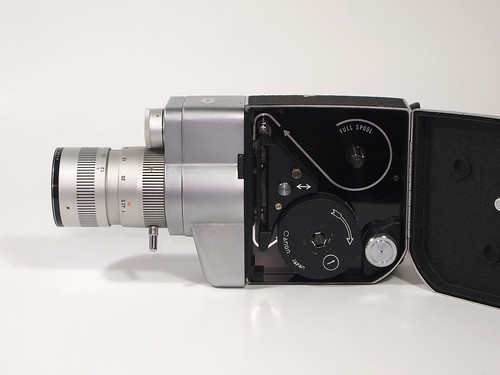

The Cine Zoom 512 was the last regular 8mm cine camera that Canon produced before Super 8 was introduced. Considering that Canon first entered the cine camera market just eight years earlier with the

Cine-8T (and, according the the Canon Camera Museum, only the third cine camera made in Japan), it's remarkable how advanced the Cine Zoom 512 is. The model number '512' is derived from its zoom factor - x5 and its widest aperture - f1.2 - a construction Canon kept to name its future cine cameras.

|

| Canon Cine Zoom 512 with power grip |

The Cine Zoom 512's specifications demonstrate the professional aspirations that the camera was aimed at:

- Fast f1.2 (stopping down to f22) 8.5-42.5mm zoom lens

- Built in CDS meter with 10 to 320 ASA range and exposure adjustment settings

- Single lens reflex viewfinder

- Wide range of shooting speeds - 8, 16, 24, 32, 48, 64 fps and single frame

- Continuously variable shutter control with stops at 'open', 1/2, 1/4 and 'close'

- Spring motor capable of shooting 4m/13ft on a single wind

- Reverse mode to rewind film for filming cross-fades

- Frame counter with single frame marks, one complete revolution for 80 frames/1 ft

The camera was also provided with a number of accessories as standard, notably the teleconverter lens attachment, increasing the zoom to 14mm-70mm; there was also the power grip, which powered the zoom action of the lens as well as having a shutter trigger. The original case that the Cine Zoom 512 came in had these accessories and more: evidently well kept, all the documentation was still there, including the warranty card which shows that the camera was purchased from one Jardine & Matheson in Hong Kong on the 6th January 1965. There was also an address label, with the first owner's addresses at an RAF base in Kent, crossed out, with a new address, and a telephone number at a Maidstone police station. There's also a price label: £22 (although no indication of when this was sold for this price). Further, the owner had included a review of the camera copied from

Amateur Cine World, dated December 3, 1964, a month before the camera was bought, and a couple of pages from

Amateur Photographer 10 June 1964: the two articles that seem to be the reason for keeping these pages are 'The Right Way to Zoom' by George Zygmund and 'Any Time is Show Time' by Anthony Wigens.

|

| Canon Cine Zoom 512 with accessories and ephemera |

Also in the case is the instruction manual and promotional leaflet, a list of authorised service facilities around the world, a close up filter, cable release and viewfinder cap to prevent light entering when used away from the eye.

|

| Canon Cine Zoom 512 controls |

Almost all the controls are on the user's right hand side of the camera, with the exception of the aperture dial and the lens' zoom handle. This suggests that, with the power grip attached, the camera is held in the right hand, which can operate the shutter trigger, while the left hand focuses, zooms and sets the aperture - although, reversing hands, the aperture dial can be fairly comfortably used by resting the right hand on top of the camera from where the middle finger can easily find the dial. The ergonomics of the camera are important given how heavy it is - 1.7kg (perhaps being able to easily change hands, whether right- or left-handed, is a tacit acknowledgment of this). This factor is mentioned in the

Amateur Cine World 'User Report': "First, the weight. A curse after you've carried it around for eight hours, but a blessing in use because of the rock steady pictures. With the heel of the pistol grip on a firm surface it is even possible to get satisfactory hand held shots on the 42.5 end of the zoom range".

|

| Canon Cine Zoom opened for loading, showing film path |

The weight itself does give a sense of solidity to the camera's construction: almost all components are cast or machined metal, with very little plastic used at all. There were a couple of minor issues relating to the age of the camera: I did find that the motor will drive 8-10 feet on a single wind now, meaning that it takes three full winds to expose one side of a roll of film, not two, as described in the manual; and there was a rubber roller on the film path which stubbornly refused to turn, which I simply removed and this seemed to cause no problems in shooting.

|

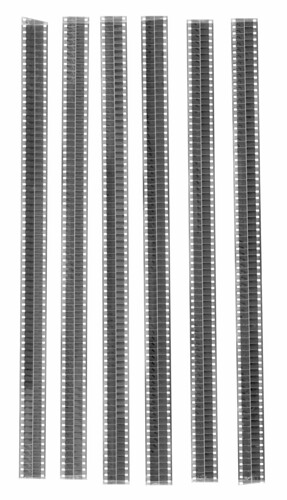

| Technopan 8 8mm film dated Feb 1970 |

For a first test with this camera, I bought (very cheaply) a roll of very old 8mm cine film. This was black and white reversal film manufactured by Shostka Chemical Plant USSR for Technical & Optical Equipment Ltd. The film was a standard 25ft length, 50 ASA, with a date on the box of 'Feb 1970'. I initially assumed that I could develop the Technopan film as a negative, thus cutting out the extra steps involved in reversal processing. I tested the film by loading a small length in the

Minolta-16 QT; the first test roll came out almost completely black and featureless. I discovered that the problem was

fixing rather than developing the film: designed for reversal processing, the film has a colloidal silver anti-halation layer. This layer would be bleached out with the negative image in reversal processing, the remaining unexposed emulsion being subsequently exposed and developed to form the positive image. However, I could develop as a negative

without fixing: for a second test, I didn't fix after development, and I was able to scan the unfixed film. This had a compressed range of tones; had I processed the film as reversal, I would probably had better results, however, this would have meant buying extra chemistry, and going through additional steps in the processing, which did not feel worthwhile with expired film, just to test an old cine camera.

|

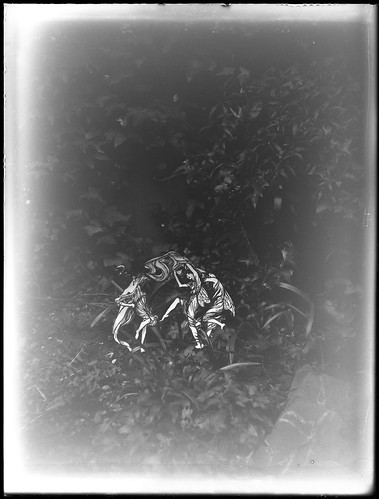

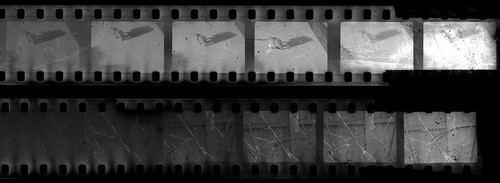

| Technopan 8 test shot |

Once I had tested the Technopan film, and was happy enough with the results, I shot the rest of the roll with the Cine Zoom 512, intending to make a short film with the results. As the camera's motor is clockwork, no battery power is needed to shoot film; the battery required for the camera's light meter is of the obsolete mercury variety, but as the battery merely activates the meter itself, the camera can be used without it (the power zoom grip takes two rather more common AA batteries, which I didn't use: I set the zoom between shots generally, rather than shooting while zooming in or out, apart from one section at the end). For exposure, I used the 'Sunny 16' rule when shooting: the manual has a table which describes the relationship of shutter speed to frame rate, while the variable shutter's positions at 2 and 4, give the equivalent of half or quarter exposure, which, when coupled with the aperture settings, provides a wide range of possible exposures.

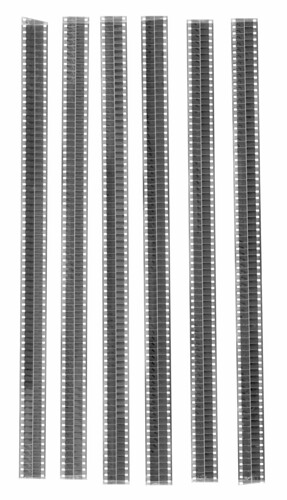

After shooting the film, I developed it in lengths of around 1.5m using stand development (some of this was done with Ilfotec LC29 at 1+100, for one hour, and some in RO9 One Shot at the same dilution; the Ilfotec LC29 appeared to give slightly higher contrast, although it was not easy to judge from the negatives themselves). With the unfixed negatives, I scanned these by taping several lengths to an A4 sheet of paper and used a flatbed scanner.

|

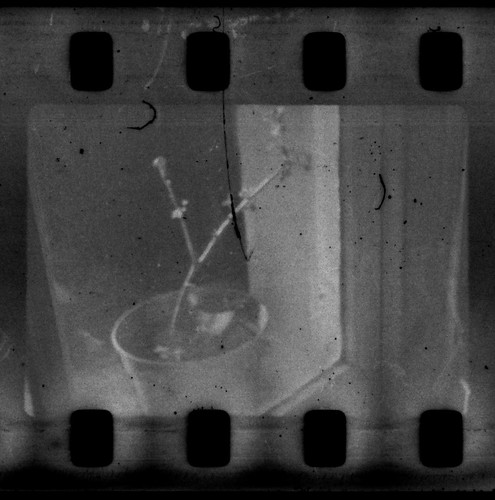

| Technopan 8 unfixed negative scan |

From the raw scan, I first flipped the image - as this was the emulsion side, the scan was a mirror image; the next operation was to invert the image to a positive and use levels to attempt to restore a good tonal range to the images. To compile the scans into a moving image file, I copied and pasted a selection across all of the rows in the scan into a new document and converted the layers into frames; setting up an action to do this in a single step in Photoshop, took much of the work out of what would otherwise have been an onerous task. I then made separate images for each of the strips, then a new document cropped from the left-hand image; the right hand image had to be rotated through 180º and the frame order reversed (otherwise this would be playing backwards). All the subsequent files created in this way were then exported from Photoshop as Quicktime movies and edited together, back into a single film using Premiere.

|

| Technopan 8 scan, inverted from negative |

Most of the footage was shot at 8 fps, some at 12, partly because I originally thought that I might only scan some short sections to animate, and doing this at as low a frame rate as possible would mean less work (additionally, the low frame rate provided the possibility to compensate for the film's loss of sensitivity in exposure); as a result, the film, mostly edited in camera, in its entirety, as has become five minutes long, rather than the more usual three minutes (some film was sacrificed for the exposure tests of course). In Premiere, I attempted to restore the frame rate to as close as how most of the film was shot, but I hadn't actually made notes when filming of what frame rates were used, so I did this by visual 'feel'.

A better test of the Cine Zoom 512 would be to shoot a roll of new 8mm film: although Super 8 killed off double or regular 8mm as a format (in much the same way that Kodak's110 cassette made other 16mm still camera formats obsolete, despite not necessarily being a better design), the film, although very rare, is still available (at the time of writing) from Foma in R100 and Orwo UN54. When I was a student, more than twenty years ago, I came across a clockwork-driven 8mm camera in a charity shop, but the shopkeeper warned me that they didn't make film for it any more. Perhaps the main reason that the double 8 format is

still available is that it uses 16mm film, albeit with an extra set perforations, meaning that continuing to manufacture the film is not as difficult as even more obscure formats, like centre-perforated 9.5mm. After Canon introduced the Cine Zoom 512, the appearance of Kodak's Super 8 format, with its bigger frame size and ease of loading, changed the home cinema market; in response, Canon took the lens that they had developed for the 512 and modified it to the

Zoom 518 Super 8 camera. The Cine Zoom 512 was the technological pinnacle of Canon's 8mm camera range, and then quickly became its swansong, the last regular 8mm camera that Canon made.

Sources/further reading

Cine Zoom 512 on the Canon Camera Museum

Historical evolution of film formats on sparetimelabs.com