|

| Offices at Night, Voightländer Bessa RF, HP5 |

I like night photography, but while traveling, or simply going out for an evening, I prefer not to carry a tripod with me. Not using a tripod is a compromise of course; this post is about how I negotiate that compromise. Having stated that, there are some very good small and compact tripods available that aren't a pain to carry around.

There are essentially two strategies, both of which I use: either a combination of a fast film with a fast (enough) lens; or steadying the camera on an immovable object for a long exposure. In terms of the subject matter for night photography, it's often a case of looking out for scenes lit up with street lights, or internal sources of illumination within buildings; light sources themselves can be the subject of the photograph.

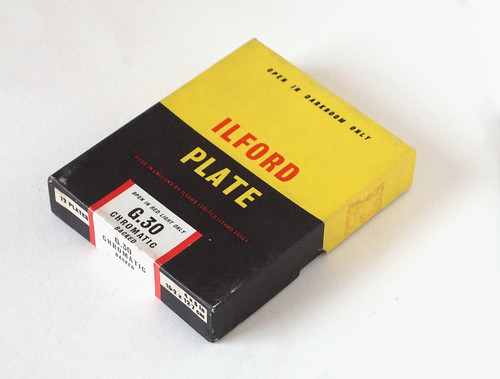

The fastest films currently available are

Ilford Delta 3200, Kodak Tmax P3200, and Fuji Neopan 1600, none of which have a true ISO as fast as the manufacturers' names suggest, being in the range of 800-1000, but these films give a 'normal' contrast range when exposed at box speed and developed accordingly. With night photography, low-light urban subjects tend to be high contrast to begin with, so push processing in an attempt to squeeze more speed out of a film can make contrast an issue (it may make more sense to pull the film to reduce contrast).

|

| Seven Dials, Canon A1 with Ilford Delta 3200, hand-held |

Hand-held

For hand-held night shots, one needs a fast film, a fast lens, and a slow shutter speed. The issues with each of these factors are: grain; a shallow depth of field; and camera shake, respectively. The first two factors can perhaps be accepted as a

fait accompli, although the appearance of grain partly depends on the developer, and wider-angle lenses have greater depth of field. Of most concern is camera shake blurring the image. The general rule of thumb for avoiding camera shake is to use a shutter speed higher than the focal length of the camera's lens. On a 35mm camera with a 50mm lens this means 1/60th (or 1/50th depending on the shutter). However, this rule of thumb is worth taking with a pinch of salt- a shutter speed one stop slower is not too difficult to hold with a steady hand, i.e. 1/30th-1/25th with a 50mm lens. Some claim to be able to hand hold speeds of 1/15th or 1/8th, which they may be able to do, but I've found that I do get camera shake at these speeds.

|

| Montmartre, Canon A1, Ilford Delta 3200 rated at 6400 EI, hand held |

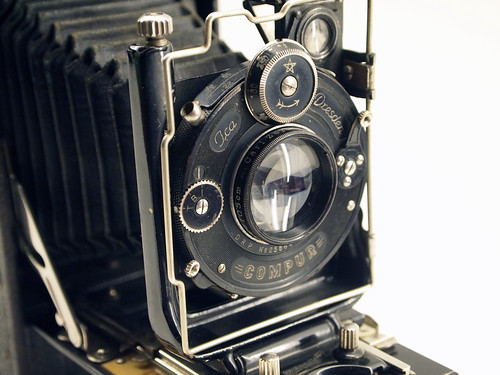

However, I don't always use a 35mm camera: a number of my recent night shots were taken with a

Baldalux medium format camera with a f4.5 105mm lens. It's not a fast lens, and the focal length suggests a shutter speed of 1/100th to avoid camera shake, although I used 1/50th for the night shots. The type of camera and shutter may make a difference to camera shake. The Baldalux is a viewfinder camera with a leaf shutter: SLR cameras suffer from 'mirror slap', vibrations caused by the mirror moving up before the shutter opens. Focal plane shutters and leaf shutters also open and close in different ways which may affect vibrations: the curtains of focal plane shutters move in a single direction from top to bottom or left to right, while the blades of a leaf shutter swing in and out in a circular motion around the lens. When using very slow shutter speeds, it might be possible to minimize shake by using the camera's self timer so that the shutter actually fires separately from the action of depressing the shutter button.

|

| Gartenstraße, Baldalux with Ilford Delta 3200, hand held |

Long Exposures

For long exposures without a tripod, the first consideration is having a camera which will sit flat while exposing. While most modern cameras will happily stand on a flat bottom plate, this is not necessarily a given with vintage cameras. I'm particularly keen on old folding cameras, and often these will only rest on the vertical with a fold-out stand, like the

Balda Rigona. Depending on the format, this is either portait or landscape: for example the image below is from a

Plaubel Roll-Op, a medium format 6x4.5 camera. Some cameras simply will not stand on their own at all: despite being level on the bottom, the

Kodak Retina is too front heavy when opened (it rests on the corner of the front cover facing at a slight downwards angle), and does not have a fold-out stand for vertical shots. Street furniture is good for places to stand a camera: benches, litter bins, post boxes, but also the flat tops of walls, railings, window sills, or even the pavement itself.

|

| Lea Bridge Road, Plaubel Roll-Op, with RPX 400 |

As with hand held shots, consideration should be given as to how to trigger the shutter for a long exposure. The usual procedure for long exposures is to use a cable release. However, without the camera secured to a tripod, it is possible to move it by the force of pushing in the cable release if the camera's just placed on a flat surface. As with hand-holding the camera, using a self timer can avoid this. One of the most useful aspects of using older cameras for night photography is that the shutters often have a 'T' setting (common on better shutters until the 1950s). Unlike 'B' for 'Bulb' which needs constant pressure to keep the shutter open, with the shutter on 'T' (for Time), the shutter opens with one press of the button or lever, and then closes on a second press. Setting the shutter to 'T', I tend to place the camera, then open the shutter with my hand covering lens in case of any movement, and then remove my hand.

|

| Mildmay Park, Baby Ikonta, Efke R100 |

I use a very loose starting point for long exposures of scenes lit with streetlights if I'm not metering for exposure: using a 400 ISO film I start with 12 seconds at f8. With exposures longer than a 1/10th second, for many films reciprocity law failure should be taken into account when calculating exposure. This actually builds in a large fudge factor, i.e. the longer an exposure, the less likely it is to be overexposed.

|

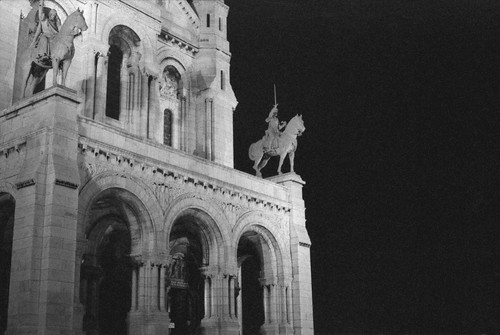

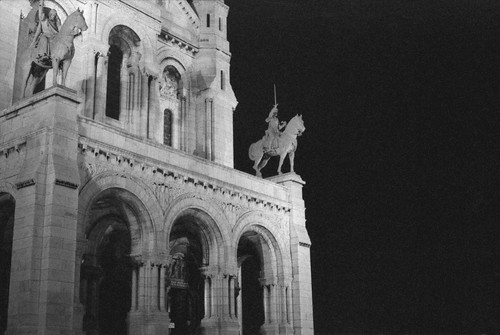

| Sacre Coeur, Canon A1, Ilford Delta 3200, rated 6400 EI, hand-held |

|

| Wallis Road, Wallace Heaton Zodel, HP5, rated 1600 EI |

|

| Zagreb, Agfa Record I, HP5 |

|

| St Giles, Canon A1, HP5 rated at 1600 EI |