|

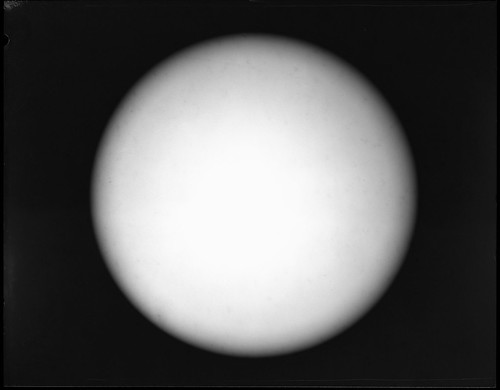

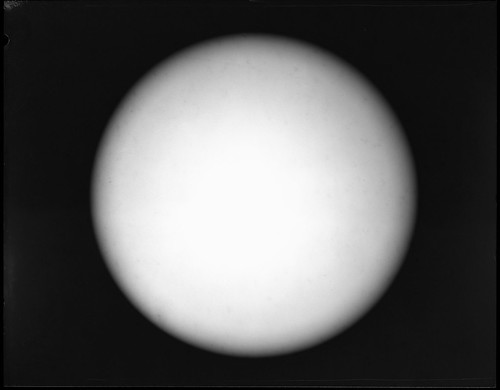

| Jupiter-8 50mm lens with Ilford FP4 |

“All lenses, regardless of format, project a circular image, and the rectangular film format must fit within this image-circle. With a small camera, a high-quality image is required within the film area, and the remainder of the image circle is disregarded. A view camera, on the other hand, requires an image-circle considerably larger than the film area, to allow freedom to use the camera adjustments. A lens’s covering power or coverage refers to the total image-circle; it is a fixed quantity, regardless of the film format, and is not a function of focal length.”

Ansel Adams, The Camera

The rectangular photographic image is a convention derived by the historically existing relationship to painting and other graphic arts (note, for example, the use of the term ‘print’ for the photographic image on paper), and this frame is built in to the technology itself. The rectangle has much to recommend it, but it is not

inherent to the photographic image. The image that a lens forms is circular; the rectangular frame is ultimately a legacy of architecture via the portable easel painting (tracing this legacy further back, cave paintings and rock art do not have definable edges: organic surfaces and surface decoration are essentially integrated). Of course, many photographs have been framed in a circular fashion - the first

Kodak camera used a circular mask to make round images, and for Polaroid cameras, the Impossible Project make an instant film with a round frame - but these are a vestigial reminder of the fact that an image produced by a lens is circular - again, it is as likely that this alternative convention of the round frame is derived from painting (the portrait miniature, as many daguerreotypes were originally presented) and architecture, and perhaps also the experience of viewing images produced by other lens-based technologies such as telescopes and microscopes, around long before photography. Given the construction of the eye, specifically that the eye has a lens analogous to the photographic lens, there is a direct relationship to human vision, in which one can never really perceive its edges; with binocular vision this becomes an awareness of a squashed oval visual field, where beyond the edge is simply an infinitude of nothing.

In Ansel Adams' quote above, the

must in "the rectangular film format must fit within this image-circle" was something I wanted to challenge. In photography, the circular image is only generally seen in extreme wide angles, such as the fish eye lens, and begins to announce its presence in the vignetting that accompanies simple lenses on cheap cameras (as with the

Diana and the

V. P. Twin). I wanted to achieve something other than a distorted image, which would obscure the object of this exercise: the distorted image would be remarkable for

those qualities, not merely for being circular.

|

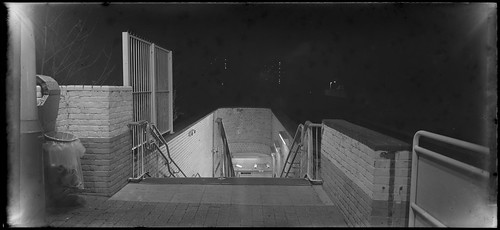

| Demaria-Lapierre 75mm Manar Anastigmat lens |

The first photographs used a 75mm f3.5 Manar Anastigmat lens, which originally came from a

Dehel medium format folding camera, of which I converted the body to make my

127 format film cutter. Although the Dehel camera was 6x4.5, a 75mm focal length lens would equally be used for a square 6x6 format; the lens itself just happened to be the right size to fit on a conical lens board for the

Micro-Technical Mk VIII. I used the Mk VIII as the folding bed can be dropped to two different positions, an important factor if this is not to intrude into the picture itself with such a wide angle lens (the angle of view itself being a relationship of focal length to image size - on the 6x4.5 negative format, 75mm represents a 'normal' angle of view). Although the edges of the image circle can be seen with the 75mm lens, the whole circle is too large to fit on the 4x5 negative. I had assumed that, as a fairly cheap triplet lens, the Manar's coverage would not be very good, but this was better than expected.

|

| 75mm Manar Anastigmat on Kodak Plus-X |

|

| 75mm Manar Anastigmat with Ilford FP4 |

As part of this exercise, I did also photograph a white wall, unfocussed, in order to see the effect more clearly. I began with the assumption that a small aperture would provide better coverage but found that this was not the case (this was something I'd read about coverage in relation to using camera movements in large format; I wanted as small an image circle as was possible, hence using wide apertures); in the shots taken with the Manar lens, the

clearest circle is that taken at f32, fairly obvious in the two comparisons below - although it is true to say that the definition at the edges is better and therefore a smaller aperture may describe a larger

usable image circle, without the circle itself being any larger - indeed, the circle appears slightly smaller.

|

| 75mm Manar Anastigmat at f5.6 on Ilford FP4 film |

|

| 75mm Manar Anastigmat st f32 on Ilford FP4 film |

When extending the lens to close focus, the image circle expands to fill whole film area, as below, with only very little distortion visible in the corners; focussing even closer could have made this distortion fall outside the area of the film completely.

|

| 74mm Manar Anastigmat with Ilford FP4 |

Although the photographs shot at small apertures produced a fairly clear circle, it was larger than the 4x5-inch film format; to produce a

complete circle, with a sharp image and clean edge, I used the Jupiter-8 f2 50mm lens from my

Kiev-4, as this has a protruding, narrow rear element - a function of it not having a focussing helical built into the lens. This meant that it was relatively easy to fix it into a lensboard, improvised with card retaining rings (holding the red infinity tab) and rubber bands. Unlike the Manar lens, the Jupiter-8 does not have a shutter, which meant that exposures had to be made by the simple expedient of removing then replacing the lens cap. This created some problems in terms of exposure: I was still working on the assumption that smaller apertures would give better coverage.

|

| Jupiter-8 50mm lens |

The first photographs with both lenses I shot on Ilford FP4, which, even rating at 64 to compensate for age (the film has a date hand written on the box 11/4/78, with the label printing dating to June 1976), made it difficult to attempt exposures of less than 1/2 a second by hand, and, in addition, the weather was sunny and bright. I did also take some photographs on

Rollei ATO 2.1, rated at 6, which did provide long enough exposure times, but the high contrast images did not really convey the effect I wanted to achieve clearly: again, I wanted the circular image to be the distinct feature of the photographs. I shot a second set of images on

Kodak Plus-X rated 25, on an overcast day, which made it easier to shoot with the Jupiter-8 lens relatively wide open. As well as not having a shutter, the 50mm lens also had a problem in that it could not be placed far back enough into the camera to achieve infinity focus, which is the reason for the images below being close focused: with the front standard racked back into the camera body as far as possible, I moved the camera and tripod forward until the image came into focus. In order to place the lens further back, a recessed lens board would be required (this should also, in theory, make the image circle smaller).

|

| 50mm Jupiter-8 lens with Rollei ATO 2.1 |

|

| Jupiter-8 50mm lens with Kodak Plus-X |

The Jupiter-8 lens made a circular image onto the film with surprisingly little distortion, except at the very edges (a side effect of using smaller apertures is that both lenses appear to show some form of internal reflections in the camera, visible as rings around the image circle itself). With edge distortion being affected by aperture, further tests at smaller apertures with a recessed lensboard might provide even crisper, clearer circular images. Although this was simply an exercise to work through - in practical terms - some ideas about the intrinsic edge of the photographic image, I do think that there is something remarkable about the idea that, in almost every photograph you have ever seen, the image formed by the lens has been cropped by the camera.

References

Ansel Adams, The Camera, Little, Brown and Company, New York 1980, twelfth paperback printing, 2005.

Alan Horder (editor), The Manual of Photography, sixth edition, Focal Press Limited 1971