For last year's

Expired Film Day, I shot some large format photographs that I used for

a piece that I made featuring a long roll of contact prints on transparency film for an exhibition. This year I wanted to do something different for the day: shoot a short film

on expired film. I've recently been using a fifty-year old 8mm camera, the

Canon Cine Zoom 512, and so it seemed fitting to attempt to shoot something with it today.

|

| Svema Och 50 black & white and CO-50D colour reversal films |

I'd previously bought a couple of rolls of Svema 8mm film from a well-known auction site, OCh-50 black and white reversal film and CO-50D daylight colour reversal film, with develop before dates of 04/91 and 05/91 respectively. I tested these films with the

Mamiya-16 Automatic: as 'regular' or 'double' 8mm film is 16mm and only split to 8mm after processing, this would fit in the subminiature camera like any other 16mm film. I shot both films at a range of exposure indices to see how much compensation I might need to make for the film's loss of sensitivity with age. Both black and white and colour films were

stand developed in RO9 One Shot for one hour.

|

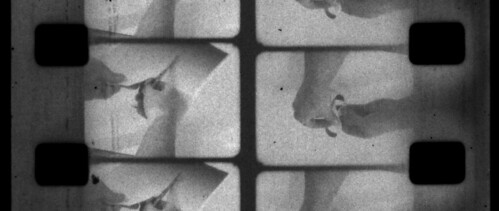

| Svema CO-50D (top) and Och 50 (bottom) exposure tests |

As both films are designed for reversal processing, they both feature a colloidal silver anti-halation layer. This means that they cannot be

fixed as negatives: the anti-halation layer would normally be removed in the bleaching stage. After developing to the negative stage, attempts to fix the film result in it darkening a great deal without the base becoming clear. Without the necessary chemicals for reversal processing, instead I developed to the negative stage, and then scanned the

unfixed negatives.

|

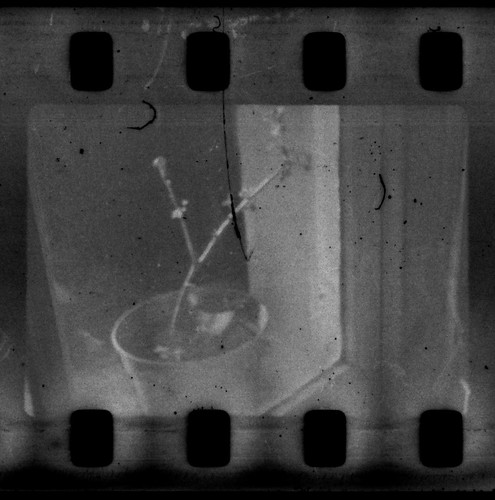

| Svema Och 50 shot with Mamiya-16 Automatic at 3EI |

The black and white film, Och 50 did not produce as good results as the colour film as it had seemingly lost more sensitivity with the passing of time; in addition, the CO-50D as a negative had a fairly uniform yellow cast, which, when removed in Photoshop, gave a better tonal range. Regardless, both films were fogged and showed typical degradation, and the small size of the negatives enhanced these qualities far more than a large format would.

|

| Svema CO-50D shot with Mamiya-16 Automatic at 12EI |

Having tested both films, I cut two five-foot lengths from each, for the practical reason that this is as much film as I can develop in my universal tank at a time. To get as long a film as possible from a five foot length of film, I shot at a low rate of 8 frames a second, meaning that, at 80 frames a foot, I'd have about fifty seconds for each side of each length of film. As well as providing a longer running time, the lower frame rate also has a slower shutter speed, critical for ensuring the film had sufficient exposure. Normally double 8mm film would be daylight loaded, and the start and end of the reel would be exposed in loading, and this would be taken into account when shooting. I denied myself the luxury of doing this, so had to thread the film through the camera's film gate in the dark, and, given the way the film has to pass through the camera twice, reload the film in the dark too.

For the

content of the film, I wanted something which would reflect the nature of the double-8 format in a structural manner. From using the film previously, I was struck by the rotational symmetry of the unsplit, full width of the 16mm film, with two sets of frames running in different directions, but didn't feel it was appropriate to show the full width of the film in its final presentation. In addition, the end of one set of frames on one side of the film becomes the beginning of the second set of frames on the other side; I imagined that it might theoretically be possible to loop unsplit double 8 film in such a way that it might run through a 16mm projector, showing both sets of frames, one upside down and running in reverse, but at the join of the film into a loop, this would

flip over and run the right way around and continuously do so. This notional film loop that could flip from backwards to forwards might take the form of a Möbius strip.

Moving from imaginary, theoretical loops to the film I made, I chose to shoot myself making a Möbius strip from a sheet of paper printed with a gradient from black to white, printed in different directions on each side, as a way of conveying the idea of one continuous surface: connected in a straight loop, the paper would have an abrupt transition from dark to light at the join, but twisted around, this join would be at the end of a gradient, dark on one side of the paper, light on the other, but continually shading from one to the other.

|

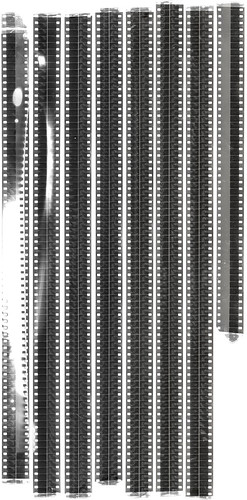

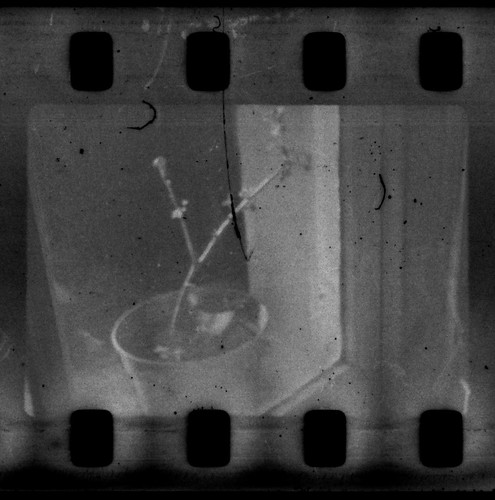

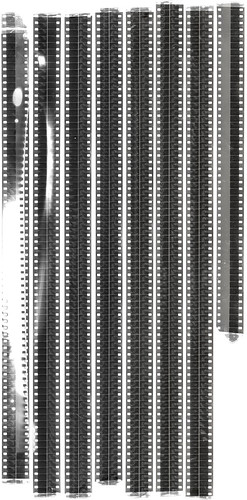

| Double 8 unfixed negative scan |

I filmed myself cutting and joining the printed paper twice, once on the Och 50 film, the second time using the CO-50D; for both, on the first run of the film through the camera, I cut the strip out, then flipping the film over in the camera in a dark bag, I shot the second side and joined the cut strip into the Möbius band. I stand-developed both films in RO9 One Shot for one hour at a dilution of 1+100; the second take I knew to be the better one, and exposing at an exposure index of 12 rather than 3 meant I was able to stop down the Canon Cine Zoom lens a small amount. However, I'd given myself nearer to 6 feet rather than 5 with the CO-50D, and it would not all fit on the developing reel: the white patches on the scan above are where the loose end of the film wrapped around itself on the outside of the reel. Once washed and dried, I scanned the unfixed negative by cutting it into strips and taping it to a sheet of paper. Inverted to a positive, the film was animated in Photoshop in individual sections, with each section also rotated through 180º and the frames reversed so that the upside down and backwards running right hand frames would then be on the left and running in the right direction; each section was then edited together so that when animated, the whole width of the film would fill the frame and it would flip over in the middle, and, in theory, loop and play all over again.